I would never be friends with a bad artist

A story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order.

Jean-Luc Godard

This story begins in a key year and is woven by threads that are not very visible among some of the art pieces in the Balanz Collection. The aim is to illuminate only certain aspects, as if to reconstruct stories, knowing that the pieces are much more than the objects presented to us and are capable of containing and radiating a wealth of memories.

In 1976, Pablo Suarez (1937-2006), a thirty-something already seasoned in the battles of art and life, exhibited a series of art works at the Carmen Waugh Gallery in Buenos Aires, in which he cited—and paid homage to—several artists not well recognized by the critics of the time, who were more attentive to other national and international trends. In that exhibition, Suarez celebrated Florencio Molina Campos, Alfredo Gramajo Gutierrez, Augusto Schiavoni, and Fortunato Lacámera, among others who—as he indicated in a prologue written by himself—had never fallen into the temptation of following the European avant-garde.

Although it was not a surprise, that exhibition was some sort of declaration. It was necessary to justify artwork, such as Maceta and Florero con hojas, of transcendental beauty and with so many reminiscences of Lacámera, which are now part of the Balanz Collection. The word “reminiscence” is not used casually. Suarez had a prodigious visual memory and boasted of not copying and never needing a model, since he remembered everything he had seen.

Pablo Suárez "Florero con hojas", 1976

The exhibition took place at a singular moment: Argentina had suffered a new military coup that began a violent repression against those who thought differently, and Suarez summed up his position with a sudden change of direction. He had left behind his distance from art, convinced of its uselessness, after having been one of the main protagonists of some of the most corrosive artistic experiences that reflected the cultural, social, and political situation of the country. He had also left behind his collaboration with the combative Confederación General del Trabajo de los Argentinos, which had inspired and made space at its headquarters in Rosario and Buenos Aires for, the art event, Tucumán Arde, at the end of 1968.

Without apparent allusions to the violent situation he was going through, Pablo Suarez critically burst onto the art scene in the face of the proliferation of the most cryptic conceptualism, a movement that seemed to him to be imposturous. And his starting point was to look at the past: to rethink how the history of art had been constructed, who had been worthy of holding a leading place in the “official” narrative, and who had been underestimated, perhaps for dealing with themes or ways of doing things that did not fit in with the idea of a succession of movements of modernity.

This anachronism led him to advocate another way of defining Argentine art, diving into some costumbrisms or folklorisms that amazed him, both for their intimacy and for the quality of their painting. In these crossings, he made references to his personal experience and quoted witticisms—sometimes phrases in the titles—from pieces by Molina Campos and Cándido López. The narrative, the simplicity, the commitment, and above all the surprising world that painting was capable of opening up, became for him a manner of speaking and a way to raise a new question about art.

But he always went for more. Not only did he boast in private that for some time he had lived by forging 18th century European artwork—something unverifiable—but on several occasions he copied himself, or rather his memory, making references between art pieces, as if inviting us to look for the differences, as it happens with Maceta, which has at least another “version” where the note on the table is rotated and with a different text. Notes, often present in the paintings of that period, are actually illegible letters, and most of the time they are signed by the artist himself, adding another temporality to the pieces, as if they were vanitas.

Pablo Suárez "Maceta", 1975

Painters without hands

“Nos cortamos las manos” [We cut our hands off], said Noemí Escandell in the mid ‘80s when she spoke with self-criticism—once democracy was recovered—about what had happened after the experience of Tucumán Arde, the emblematic artwork of 1968, which, far from being an object, was a real mechanism of significance that continued to be recreated for decades and had also functioned as a rupture. It was a limit through which artists had become aware that their critical action led them to discover the meaninglessness of art.

Tucumán Arde had all the condiments: a collaborative artwork, made outside official institutions, presented at the CGT de los Argentinos in Rosario and then in Buenos Aires, where it was censored. It was artwork that had proposed overinformation through a study of the critical situation in Tucumán after the closure of sugar factories promoted by Onganía’s de facto government. It was artwork that had included trips and deceptions through the announcement of the First Biennial of Avant-Garde Art, that had joined the denunciations of the central workers’ union, which had proposed to cross art in every sense, bringing together sociologists, communicators, artists, writers...

Tucumán Arde was the last milestone of a year in which people from Rosario, Santa Fe, and Buenos Aires had converged in an institutional criticism, especially of the Di Tella Institute but also of all the institutions that began to censor or fear the action of artists, as it happened with the Braque Prize of the French Embassy and its attempt to avoid questioning, by requesting to see the artists’ projects beforehand out of fear of the claims that could be made in support of the French May.

“Nos cortamos las manos,” Escandell said, and she was talking about a decision that had been taken with a certain naturalness, despite the fact that not everyone shared the same convictions. It was what was called the transition from experimental art to political art, which was simply a questioning of one’s own practices and what to do to prevent artistic production from being absorbed by cultural institutions or the market. To question art was also to stop creating with one’s hands. Conceptualism—perhaps we should speak of a new form of conceptualism—had just appeared on the scene, and art maintained a root of handcraft, although no longer tied to representation or non-representation but to a question about what to do through traditional techniques.

But it made little sense to continue discussing what painting was and to add more devices to those created by artists to cause discomfort in competitions or in the exhibitions of official institutions. There were other urgencies, and it was a question of what to do to generate revolutionary, transforming pieces that could not be hung on the walls of bourgeois houses—even more so in a context in which the assassination of Che Guevara, the French May, the Vietnam War, and above all Onganía’s dictatorship were the daily themes. Obsessed with efficiency, in the sense of producing artwork that helped to transform reality, criticism of the art system was not enough. It was of little significance to have questioned academic painting, and it only seemed to show the uselessness of their own productions. It no longer made sense to denigrate the very emblematic institutions of the 1960s, like the Di Tella Institute.

“Nos cortamos las manos,” Escandell said, and spoke of a painful sensation that caused her to feel that she had been denied a way of expressing herself. Juan Grela—one of the teachers of young avant-garde artists from Rosario, like Juan Pablo Renzi—asked Rubén Naranjo, another protagonist of Tucumán Arde, “¿Usted para qué quiere hacer la revolución? ¿Para que toda la gente pueda vivir mejor y disfrutar de cosas como el arte? ¿Pero entonces por qué abandona el arte?” [Why do you want to start a revolution? So that all the people can live better and enjoy things like art? But then why are you abandoning art?]

It is always time to not be an accomplice

Juan Pablo Renzi (1940-1992) had been one of the main protagonists of the so-called 1960s Avant-Garde, and at some point, he even boasted of having been the true “author” of Tucumán Arde—something contradictory for a collective work that questioned authorship. However, his own partner, María Teresa Gramuglio (author, together with Nicolás Rosa, of the manifesto that accompanied the piece), recognized that in every group there are those who have a more leading role.

The truth is that Renzi had been one of the main promoters of many of the experiences carried out, first in Rosario and then in Buenos Aires, since the early ’60s. This protagonism was what led him to actions such as publicly presenting the manifesto “Siempre es tiempo de no ser cómplices” [It is always time to not be an accomplice] in rejection of the prior censorship in the Braque Prize or intervening in Rosario in a lecture by Jorge Romero Brest to read a statement known as “Asalto a la conferencia de Romero Brest” [Assault on the Romero Bres Conference], a foretaste of the avant-garde group refusing to accept finances from the Di Tella Institute for their Experimental Art Cycle.

By then, a critical reflection that had begun a few years earlier had already been consolidated, and it was aimed at the institutions and what was legitimized as art. The art piece Paisaje con gran nube, from the Balanz Collection, represents a fundamental moment in which the artist openly questioned the most visible art of those years in Rosario, a trend that he and his fellow artists called “pintura mermelada” [marmalade painting].

One of the blows perpetrated by Renzi was aimed at what was legitimized in the salons, and for that, it was necessary to take over a contest through juries that supported the new trends. That is why he actively participated in the First Salón de Pintura Joven del Litoral, organized by Gemul (Grupo de Estudiantes de Medicina de la Universidad del Litoral), at the Castagnino Museum in Rosario. The jury was finally composed of Kenneth Kemble and Jorge López Anaya, for Gemul, and Miguel Dávila and Hugo Ottmann, for the exhibitors. There, Renzi presented two pieces and received the First Prize for Gran interior rojo. The other was Paisaje con gran nube, one of his initial conceptual proposals, this time through painting.

Juan Pablo Renzi "Paisaje con gran nube", 1966

These were not pleasant times, the battle for art in Rosario had begun, and the young artists were moving forward strategically, showing their dissidence with the “academicism” into which several of the artists, who in the early ‘50s had formed the questioning Grupo Litoral, had fallen. But the lack of persistence meant that the period of artistic ferment was very short, barely a few years, until practically all the avant-gardists left art for politics, some of them for good.

The wound to the interior of the Rosario art scene had been opened, but the defeat at the salon was quickly wiped out by the more traditional sectors. It took 30 years for Kemble to return to be a juror in a competition in Rosario. He himself commented on what had happened: “Me odiaron y no me invitaron más” [They hated me and never invited me again].

For love and for horror

“No nos une el amor sino el espanto” [We are not united by love but by horror], says Jorge Luis Borges in one of his poems. And the verse was multiplied to speak of encounters where different people cross paths and come together, often leaving aside differences. Whether out of love or horror, there was a significant cultural crossover between four major artists, represented by works in the Balanz Collection: Pablo Suárez, Juan Pablo Renzi, Oscar Bony (1941-2002), and Roberto Jacoby (1944). All of them were protagonists of the Avant-Garde of the 1960s; they assumed an ethical and political commitment, but above all they were always “contemporary” and became referents for many artists.

Among them, some were friends, others not so much, but they established a permanent dialogue through their art and also through silence, when they decided to distance themselves from artistic practice. It was Renzi who introduced Pablo Suarez to Augusto Schiavoni’s work. He was an artist to whom Renzi paid homage through intimate pieces, similar to those of Suárez. There was a need to return to painting in the mid ‘70s after having abandoned art.

It was about painting the immediate environment, seeking universality in simplicity. Returning to manual activity. To develop—as Suárez said—a way of doing, to which, as he confessed, he was constantly going back and forth, as if this “small subject” were a place of reunion.

Oscar Bony had also returned to painting at that time, after devoting himself for some time to photography. Cielo, a painting from 1975, part of the Balanz Collection, is one of the artist's transpositions of a series of photographs he had taken earlier that year on a trip to El Bolsón. Another manner of speaking—and also resuming old loves—, which he said was inspired by his daughter, Carola, and by the Renaissance paintings that had amazed him. In fact, he used to talk about the impact of a painting by Botticelli that he had seen on a trip to Europe a short time before.

Oscar Bony "Sin título (Serie: Cielos)", 1975

Although there seems to be a certain hyperrealist intention in this shift from photography to painting, there is a search that links these pieces to what we could call a premature return to painting, an intention to put his hands back into the dough, to return to making handcrafts.

The relationship between Roberto Jacoby and Pablo Suarez was the closest among these four protagonists. Road companions since the ‘60s, they maintained their friendship, among other things, due to their mutual respect and recognition. Although they were very incisive and critical (in Pablo's case we should add “acid”), they coincided and shared crucial moments. They even painted some pieces together—finally signed by Jacoby—to try to earn some bucks in a contest.

“Yo nunca sería amigo de un mal artista” [I would never be friends with a bad artist], said the director of the Centro Cultural Recoleta and critic of Página/12, Miguel Briante in the early ‘90s. Something that was applicable to this relationship. But common interests also generated other encounters between artists. One of the most significant cases was that of Luis Fernando Benedit (1937-2011) and Pablo Suarez. Although both had experiences related to the Argentine countryside, their training and outlook were different, although they always shared the same beliefs, popular knowledge, and stories developed by artists such as Molina Campos.

In Benedit's case, the countryside permeated much of his artistic production. It was a recurring question that included historical, social, and political studies but also pays tribute to those who, with a certain simplicity, “spoke” through their characters, hence the prominent place he gave to FMC (Florencio Molina Campos) through pieces such as FMC, por mal nombre El León (con caballo amarillo), 1989, and Homenaje a FMC, 1992, both in the Balanz Collection.

These coincidences led them to share the Taller de Barracas, of the Fundación Antorchas, as “maestros”: one of the first experiences in generating a place of production, an art clinic, at the beginning of the ‘90s. The space was mainly aimed at helping to train artists interested in the production of objects, sculptures, and installations. The latter productions were the most controversial in those years, since they were walking, living pieces, aimed at all the senses and by which painters felt threatened.

It was there that young creators came together, such as Nicola Costantino, another artist very well represented in the Balanz Collection, who developed several of the art pieces that contrasted the “lighter” approaches of the Rojas Cultural Center—or “brighter,” according to the expression that several of the artists preferred over the adjective given by Lopez Anaya.

Suarez, by that time, was already developing a sculptural piece, where several of his formal and narrative interests converged. One of the characteristics were his characters’ bulging eyes, like Molina Campos, although he added the memory of his father’s face, who hanged himself after an economic crisis.

The neighborhood “chongos” appeared, those that Gumier Maier recognized made him horny. Muscular men, coming from proletarian neighborhoods, with a strange beauty because of their somewhat deformed bodies. The muscles sculpted by the force of lifting heavy objects contradicted their slightly thinner legs, as a possible consequence of childhood rickets. Those “chongos” were characters in many simple narratives, scenes accompanied by some legend or popular saying. A gay poetic that radiated eroticism.

Suarez was one of the artists of his generation who maintained the best relationship with the group that gathered around the Rojas. Not only was he an interlocutor and a friend, but he himself adopted techniques, such as using pearly nail polish to paint surfaces. This is the case of El Perla - Retrato de un taxi boy (1992), one of the most significant artworks in Suarez’s production and part of the Balanz Collection.

Pablo Suárez "El Perla (Retrato de un taxi boy)", 1992

Nothing worse than critics and curators

In the exhibition held at the Carmen Waugh Gallery in 1976, Pablo Suarez decided to give a prologue at the show to avoid not only misleading “interpretations” by critics and curators but also to denigrate those who constructed discourses based on the artists’ work, confusing “depth with complexity”. He repeated these reflections over the years, always interested in preventing artwork from having to be explained. One of his criticisms of the art system was aimed at the mediators, an attitude that was further deepened in the 1990s, when curators and new knowledgeable and decisive agents began to proliferate, taking such a leading role that they began to overshadow the artists summoned for their exhibitions.

Romero Brest and, later, Jorge Glusberg were the main protagonists of the art scene for decades, marking alleged paths in line with international movements. He was less stung by Gumier Maier because of his status as an artist and his position on art. But other voices were starting to make their voices heard in the ‘90s: Fabian Legenblik, Julio Sanchez... and particularly, the polemic, Jorge Lopez Anaya, who took center stage when he resolutely attacked certain artistic practices by contrasting them with the productions of some artists linked to the Rojas.

“Debo hacer una recomendación. Muchos de ustedes son pintores. ¿Conocen una asociación que se llama ´Alcohólicos anónimos´, que es buena para curar a los adictos? Por motivos similares se podría crear una de ´Pintores anónimos´ para salvarse de la afición a la pintura. Ya Duchamp nos había advertido de los peligros de la trementina” [I must make a recommendation. Many of you are painters. Do you know an association called Alcoholics Anonymous, which is good for curing addicts? For similar reasons, one could create a Painters Anonymous to save oneself from the hobby of painting. Duchamp had already warned us of the dangers of turpentine], said Lopez Anaya at the end of his speech at the International Art Criticism Conference in 1992.

Those were convulsive years, the restoration of democracy had brought in parallel a cultural effervescence that overflowed across all artistic and social boundaries, while AIDS ravaged like a plague.

Postmodernity appeared as an unresolved question, perhaps because nobody understood why it was necessary to introduce a new narrative—actually, an anti-narrative—which was supposed to overcome others. While Lopez Anaya delved into the weak thought promoted by Gianni Vattimo, Renzi wondered about the place of art, looking for a totally different answer. Hence, against the neoliberal currents of those years that marked most of the discourses of postmodernity, he reflected on how a new, critical art could be made. That is to say, a production that was sufficiently questioning, with regard to any dogmatic discourse, including the postmodern discourse itself.

This conviction led him to an incessant search for new ways of expression through painting. Constelación del martillo mayor y el martillo menor, from 1988-1989, and Sin Sol, from 1992, both part of the Balanz Collection, are two key pieces from that period. A path that was cut short due to his premature death.

Strategies of Joy

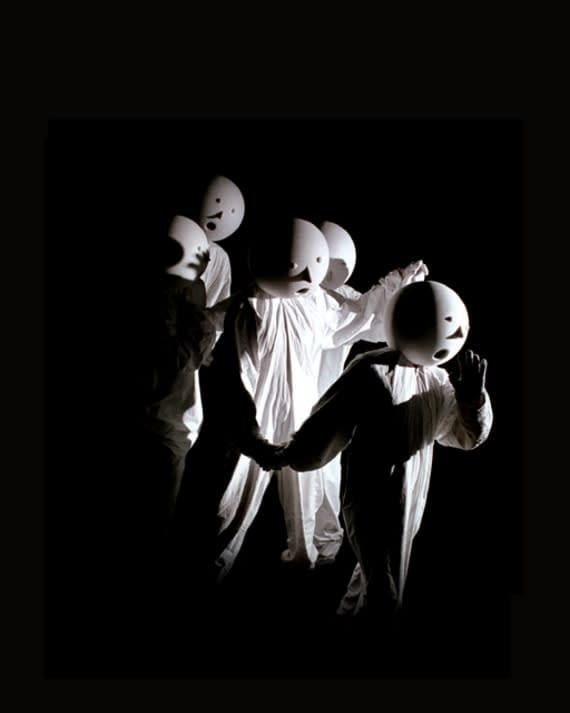

The Balanz Collection includes the photograph La procesión va por dentro (2005), by Roberto Jacoby. It is an image obtained in the Darkroom installation, where a group of performers, with identical masks, move blindly in a totally dark space. The view is that of the spectator—only one at a time—who was invited to be a voyeur through an infrared camera. There was an added bonus: he recorded the video at the same time as he watched.

The performers acted hesitantly. No one knew what the other was going to do. And Jacoby's instructions were mostly negative: no talking, no gesticulating.

Roberto Jacoby "La procesión va por dentro", 2005

The artist, one of the last to return to artistic practice after the experience of Tucumán Arde, had developed research and projects related to the media, but his interests led him to delve into sociological studies and to write lyrics for Virus in the 1980s, one of the central bands of that decade in Argentina.

Therefore, this supposed distance from art should be redefined, since it was more about other pursuits. His interest in social issues and his questions about the “strategies of fear” and the “strategies of joy”—to which can be added the “technology of friendship”—placed him in a central place in art since the return of democracy in 1983 and especially since the late ‘90s when he began to work more intensely on collective projects, such as the Proyecto Venus, which proposed a mechanism of exchange in a group through the generation of a new currency, the Venus, as a foretaste of what would be the terrible social and economic crisis of 2001.

What would be the distance between Proyecto Venus and Darkroom? Perhaps this is the question that allows us to reflect more deeply on the art system itself. A critique taken to its limits by the individualism of the spectator who snooped on those masked beings.

As a beginning

Roberto Jacoby decided to devote himself to art after visiting an exhibition of Pablo Suárez in 1964. From then on, they were united by a deep friendship. And although he was never nostalgic, some of his memories seem to reveal their complicity.

In 2003, at Malba, a round table was held, promoted by Jacoby through the Proyecto Venus, with the controversial title “Arte rosa light/Arte Rosa Luxemburgo,” to contrast the supposedly uncommitted art of artists linked to the Centro Cultural Rojas, with other expressions of political art of denunciation that anticipated the 2001 crisis and accompanied the social protest.

At the meeting, Jacoby recalled youth experiences from the 1960s, when artists with the most diverse artistic tendencies coexisted but who, in the face of explicitly political events, such as the Vietnam War, agreed on their denunciations. “Esto hacía a la riqueza y la vitalidad del ambiente cultural que es algo que a mí me gustaría preservar” [This made for the richness and vitality of the cultural environment, which is something I would like to preserve,] he said.

In mid-2018, in an interview conducted by Juan Laxagueborde, in the framework of the exhibition “Traidores los días que huyeron,” which brought together little-known art pieces from different periods created by Jacoby, he elaborated on the relationship between art and politics, warning that politics is always conjunctural, but art thinks post-revolution and was made to endure.

A few months later, when he received the Artistic Career Award, he recognized the importance of the social function of art but not for its educational, pedagogical, or testimonial function. “Creo que el arte,” [I believe that art,] he said in an interview for the National Ministry of Culture, “si tiene algún sentido, es el hecho de que es la única actividad humana adulta que no tiene por qué explicar una finalidad o una utilidad; el arte es un juego y crea sus propias reglas. Y el juego es algo fundamental en la humanidad. Que exista el juego es una función social importantísima. Eso es lo más importante del arte. Y jugar con reglas que no existían antes. La diferencia entre los juegos de los niños y el arte es que los niños juegan con reglas que preexisten. El arte, en cambio, crea sus propias reglas. Cada artista funda su propia constitución; funda las reglas con las cuales va a jugar. Y esto es, justamente, lo que más se parece a un ejemplo de la libertad” [if it has any meaning, it is the fact that it is the only adult human activity that does not have to explain a purpose or a utility; art is a game and creates its own rules. And play is something fundamental to humanity. The existence of play is a very important social function. That is the most important thing about art. And playing with rules that did not exist before. The difference between children’s games and art is that children play with pre-existing rules. Art, on the other hand, creates its own rules. Each artist founds their own constitution; they found the rules by which they are going to play. And this is precisely what best resembles an example of freedom].

Fernando Farina

Presidente de la Asociación Argentina de Críticos de Arte