As we know, contemporary art does not follow specific construction rules, nor does it ascribe to precise disciplines or materialities. As a phenomenon that embodies a view of the world and its events, rather than a technical or formal requirement, it can adopt the most varied configurations, although these generally respond to the questions and sensibilities of our time. Contemporary art is expected to respond to the demands of the present. But these demands are often met, paradoxically, through critical incursions into the labyrinths of the past, public history, social memories, and personal recollection.

A good part of recent artistic production refers to specific socio-political circumstances, community experiences, open wounds in history, and subjective perceptions of the common past. Another usual line of work, within this same path, is the one that investigates the history of art itself; the one that quotes or recovers artists, art work, or procedures belonging to the plastic reservoirs of other times, with attitudes that range from respectful homage to the insolent heterogeneity of postmodernity.

These strategies allow us to comment on our own context from a certain critical distance, although we must not forget that artists are not true archeologists. Jorge Luis Borges said that “el pasado es arcilla que el presente labra a su antojo, interminablemente” [the past is clay that the present shapes to its liking; interminably]. Modeling that clay and making it speak to today's eyes is one of the obvious purposes of these critical-analytical practices that are so common in some contemporary creators.

Rummaging around at home

Art history has always played a fundamental role in the development of any artistic discipline. One learns by looking at the masters of the past, analyzing their modes of production, testing their techniques, and assimilating their contributions. But the tendency to thematize the history of art, to put it under the magnifying glass within the artistic work, constitutes a self-reflexive operation that acquires a specific meaning, as of modernity. The modern painter is not only dedicated to painting but also exposes a theory or a vision of the world through his painting. Contemporary art continues this reflective movement by including modernity itself as a system of thought to be analyzed, sometimes critically, sometimes ironically, and sometimes from nostalgia.

Casa Baeta X (2014), by Juan Araujo, dives into the relationships between color, habitable space, and modernism, based on the pictorial reproduction of photographs of the Casa de Olga Baeta, an avant-garde construction designed by Vilanova Artigas in the city of São Paulo in 1956-57. Araujo's washed-out tones and pedestrian representation contradict the heroic status of this icon of modern architecture, while still highlighting its formal sobriety, precise geometry, and elegant lines.

On the other hand, the homage to Piet Mondrian in Mathew Mercier's Drum and Bass series (2002 to present) does not hide its hint of sarcasm. In it, the artist arranges common, banal objects in primary colors (red, blue, and yellow) on black shelves and white walls, completing the strict plastic values Mondrian employed in his art work. In the search for universal harmony carried out by the Dutch painter, Mercier contrasts the momentary and contingent balance of some inconsequential elements, although much closer to the everyday sensibility of the viewer.

In a series of artwork, Luis F. Benedit pays homage to Florencio Molina Campos, a painter little recognized in the history of Argentine art, perhaps due to his simple figuration, with a markedly costumbrist tone. In his tribute, Benedit usually names his referent (almost always with the acronym FMC); however, he uses an image so foreign to the one popularized by Molina Campos that the homage would be very difficult to detect without the explicit mention of this author that usually appears in the titles of the pieces. On other occasions, the citation to a model may cause more uncertainty than clarity. This happens, for example, in Retrato de un argentino. Beckmann E (1997), in which Benedit takes inspiration from a painting by, German artist, Max Beckmann to elaborate a portrait of his own father.

These obscure, erudite quotations are very demanding on viewers, especially when the transposition of the referenced work departs markedly from the original. The central figures of Max Gómez Canle's Be a Fortress (2003) are the geometric, three-dimensional translation of the protagonists of Roberto Aizenberg's painting Padre e hijo contemplando la sombra de un día (1962), set in a sort of landscape characteristic of Flemish painting. Here, one must be aware of Gómez Canle's confessed admiration for his predecessor in order to detect the relationship between the two works; otherwise, it is almost impossible to establish the link.

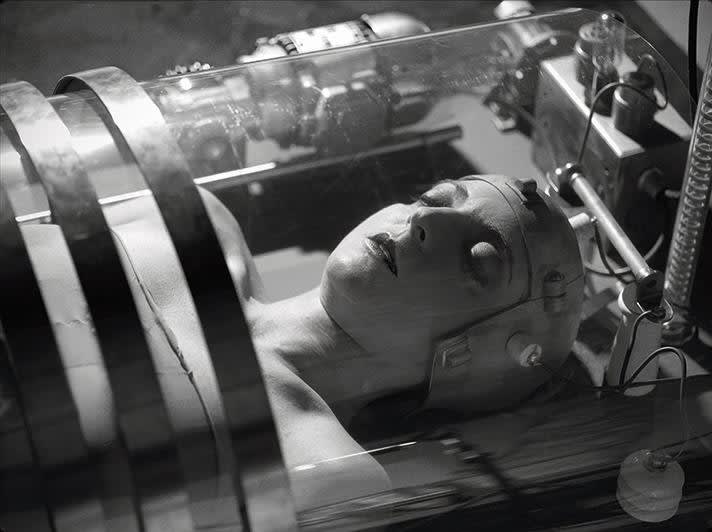

However, it is usually a more common practice for artists to explicitly state the sources of their quotations, although this does not always exhaust the possible references. This is what Nicola Costantino does in most of the photographs based on images from different visual fields, such as cinema (Nicola como María, según Metrópolis I y II, 2008), painting (Nicola según Berni, 2008), or photography itself (Nicola como Gloria Swanson, según Edward Steichen, 2008). In these pieces, Costantino pursues parody, estrangement, and, perhaps, also the displacement of the— male—authors who built certain images around women. In other pieces belonging to the series Crónicas de la mujer menguante (2015), there seems to be a veiled reference to Grete Stern and her brilliant surrealist construction of feminine universes.

Nicola Costantino "Nicola como María, según Metrópolis II", 2008

In Vik Muniz's Pictures of Dust (Donald Judd, Untitled, 1965; Barnett Newman, Here III, 1965-66; and Carl Andre, Twenty-Ninth Copper Cardinal, 1975), 2000, the quotation procedure reaches a surprising degree of literalness in order to delay the recognition of its material and conceptual procedures. The photograph emerged from the Brazilian artist's incursion into the archives of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Based on careful research, Muniz selected a set of images from exhibitions of minimalist and post-minimalist art and painstakingly reproduced them using the dust contained in the museum's vacuum cleaners (the work belonging to the Balanz Collection is based on a record of the exhibition Sculpture from the Permanent Collection, 1982). In this way, the texture observed in the photograph is not the product of aging, nor the grain of the surface, nor the absence of light, but the specific characteristics of the material captured by the camera. At the same time, Muniz confronts the solidity of the metallic sculptures with the volatility of the dust that reproduces them, but also with the fleetingness of the memory of their public presentations. We could even think of dust as the final destiny of erosion (of metals) or as the set of particles that, insignificant and marginal, threatens the stately power of consecrated works of art.

It is not common for the materials or the media of an artistic production to have such a forceful conceptual value. However, some authors manage to find the right resource at the right time. This can be said about the pieces that Tomás Espina started in 2002, from the mass media images of the conflicts in the streets of Buenos Aires caused by the economic and institutional crisis of December 2001. In the elaboration of these pieces, Espina uses gunpowder on canvas (later he will also use paper), which he then ignites, provoking a series of controlled explosions. This results in the screenshots of the television and graphic media on the piece being “marked with fire”, as well as the events reproduced on it, which marked the history and destiny of Argentina with fire. The pieces also have the characteristic smell of burned gunpowder, which gradually deteriorates over time, indicating the surreptitious persistence of latent violence.

The turns in the history of art do not always lead to obvious readings. Sometimes, it is necessary to know the contexts in which certain quotations arise to understand the motivations of their authors. There are operations that must be apprehended in the light of the mood of the times, expanding the system of artistic, cultural, and historical references, as is the case, for example, of Maceta (1975), by Pablo Suarez.

In the 1970s, Suarez recovered the work of some classic Argentine painters—Fortunato Lacámera, Alfredo Gramajo Gutiérrez, Florencio Molina Campos, and Augusto Schiavoni, among others—who, in his own words “were never tempted by the nostalgic Europeanism that was a guarantee of success for so many others.” With this act, to a certain extent, he disavows his time at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires, the institution with an internationalist vocation, where he had developed an important part of his career. But the serene, everyday environments, which Suárez takes mainly from the paintings of Fortunato Lacámera, are also scenes of catharsis in turbulent times, such as those experienced by Argentina towards the middle of the decade.

Pablo Suárez "Maceta", 1975

In La catástrofe de la percepción (1982), Marta Minujin resorts to Hellenic sculpture to give body to a time of uncertainty. In the context of the theories of postmodernity, with its slogans about the fall of the great narratives, the disappearance of truth and reality, and the end of utopian projects, the Argentine artist depicts the crisis of the Greek ideals of beauty and knowledge, which were the foundations of Western civilization, through a fragmented head incapable of reconstructing the unity of the world around it.

Adrián Villar Rojas’ work takes place several years later, when the loss of that unified humanist vision was no longer experienced as a tragedy. Moreover, it is the vestiges of that vision that give life to monumental installations, such as The Theater of Disappearance (2017), originally presented on the terrace of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Here, fragments of the past, culture, and art—most of them taken from pieces on display at the museum—interact with present-day human figures in a sort of post-historical banquet that crosses epochs, civilizations, and geographies. It is composed of sculptural ensembles, of pristine white, that represent scenes that give rise to a visual narrative, even if what is happening is not immediately comprehensible.

The selection of the objects reproduced does not respond to any enunciative or formal logic but to the most absolute subjectivity. This unique perspective, which gives rise to whimsical collections and inventories, appears frequently in the work of certain, rather young, contemporary artists. It is seen, for example, in Setting Up a System. A World Without You (2015), by Iván Argote: an accumulation of papers, posters, comics, texts, and photographs from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, through which the Colombian artist offers us a highly personal look at the decades immediately preceding the one in which he was born. The non-formalized choice of references does not imply arbitrariness. The phrase “Is This Tomorrow” in the forefront (which by its structure expresses a question, although the corresponding punctuation mark is missing), seems to refer to the exhibition This is Tomorrow inaugurated at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in August 1956, the official birth certificate of pop-art. The cartoon paintings in the background reinforce this affiliation, although they show police confrontations and persecutions more akin to the political climate of the Cold War than to the celebratory spirit of pop.

Paulo Nimer Pjota's operation, on the other hand, is extremely audacious. His The History of Colonialism (2017) reduces the ambitious project of its title to the confrontation of a few seemingly unconnected elements: some “primitive” figures, some vases, different emojis, a monochrome canvas as a support. In reality, the scarcity of elements broadens the possible interrelationships. What is truly overwhelming in this art piece is that these links are delegated, to a large extent, to the viewer, to their associative capacity, to their historical and cultural memory, to their interest in exercising a deep critical reading.

Paulo Nimer Pjota "The History of Colonialism", 2017

Finally, subjectivity appears in some artistic works in the form of an immersion in family images, collective memories, and personal recollections. In Autorretrato (1984), Marcos López dives into the photographs, the social environment, and the domestic spaces that shaped his childhood. As in the classic (pictorial) portrait, the environment here is much more eloquent than the semblance of his face on a bedside table. Along these lines, Rosalba Mirabella appropriates the format of school photography in the production of El colegio (2009). Through the laborious creation of a model, she reconstructs the distribution and poses of a group of women who provide testimony of their passage through a religious school, a ritual that has been lost over time, until it has become the trace of an unrecognizable past.

History, fable, and testimony

Just as the artistic past appears recurrently in an important part of contemporary art, numerous specific political, social, and cultural circumstances find their place in that same production, not only in the form of a contextual perspective that allows us to understand thematic or conceptual aspects of the art pieces, but also as raw data or documentary references that can be approached from an aesthetic point of view. Artistic procedures are clearly different from those used by historians. Perhaps for this very reason, the particular approach of artists to certain aspects of social reality promotes unsuspected and diverse thoughts and points of view.

In País/Tiempo (2007-13), Óscar Muñoz reproduces the front pages of Colombia's most popular newspapers (El País of Cali and El Tiempo of Bogotá) with decreasing intensity, causing their news to dissipate as the pages are turned. The fading effect points to the relationship we establish with the events that assail us day after day; events that, almost at the same time they are brought to our attention, are gradually buried by the insistent mechanisms of a systematic oblivion.

Adriana Bustos recalls another procedure that has been used to provoke oblivion. In her installation, Burning Books IV (2017), she copies the covers of erotic books and magazines, censored during authoritarian regimes, and confronts them with images of burning publications in different historical moments. Meanwhile, Chilean artist, Voluspa Jarpa, performs the reverse movement: she brings to light declassified archives, secret files, and records destined for obscurity that, when brought back into circulation, reveal the persecutory and repressive mechanisms that operated, for a long time, in the shadows in some countries of the Latin American continent (Jair José - em cualquier lugar, 2013).

In Fisuras como metáforas (2017), her compatriot, Catalina Swinburn, makes a cloak from the images of an archaeology book that reproduces destroyed or displaced Iranian historical sites. Through this action, the artist transforms lost treasures into an object of protection, as if the spiritual effluxes of those treasures could still impact the bodies of those of us who survive cultural barbarism.

In the series Fotógrafo dominguero (2013), Carlos Garaicoa, a Cuban contemporary artist, makes a meticulous record of the facilities of a steel factory from the socialist era in the town of Donetsk (Russia). In it, he shows us the collapsed building, destroyed furniture, and abandoned partisan images, as residues of a political system that used to keep the world in suspense but does not even seem to deserve historical preservation today. The look is, at the same time, nostalgic and devastating. Coming from an artist born in one of the still resistant bastions of the communist project, the photographs acquire perhaps a more dramatic character, insofar as they point out a latent destiny in the present moment of a country that is holding on with difficulty to the glories of its revolutionary past.

On the other hand, in the installation Puente Pearson (2014), Garaicoa displays the restorative sense of artistic practice. On a record of the Magdalena River in the town of Honda (Colombia), the artist reconstructs the structure of a bridge destroyed by the erosion of its pilasters through thin lines of threads held by pins. The ghostly presence of this reconstruction perpetuates the memory of the local inhabitants, for whom the Puente Pearson was a fundamental part of their lives.

The architectural structure, analyzed by Los Carpinteros in Estudio de Hans Poelzig, solid three (2016), seems expurgated of any communal functionality. Its monumental presence, its rationalist volumes, and even its elegant lines are not enough to endow it with a meaning that is not purely plastic, fruitless, or superficial. In their approach to the work of the expressionist architect, Cuban artists seem to prefer to rescue aesthetic values over practical ones, the most mundane materiality over the modernist discourses of efficiency and social destiny.

This perspective, which is suspicious of heroic narratives, official ideological constructions, empty voluntarisms, and messianic projects, appears frequently in productions of a somber character. It is, for example, in the genealogy of Patria (2011), by Cristina Piffer: an installation in which a block of paraffin and grease, with the word after which the piece is titled, rests on a stainless steel countertop. The materials here are highly significant. They refer to the livestock production that forms the basis of Argentina's economy but also to dark episodes in its history, such as the annexation of productive fields after the military campaign geared towards the expulsion of native peoples, cynically known as "The Conquest of the Desert" (1878-1885).

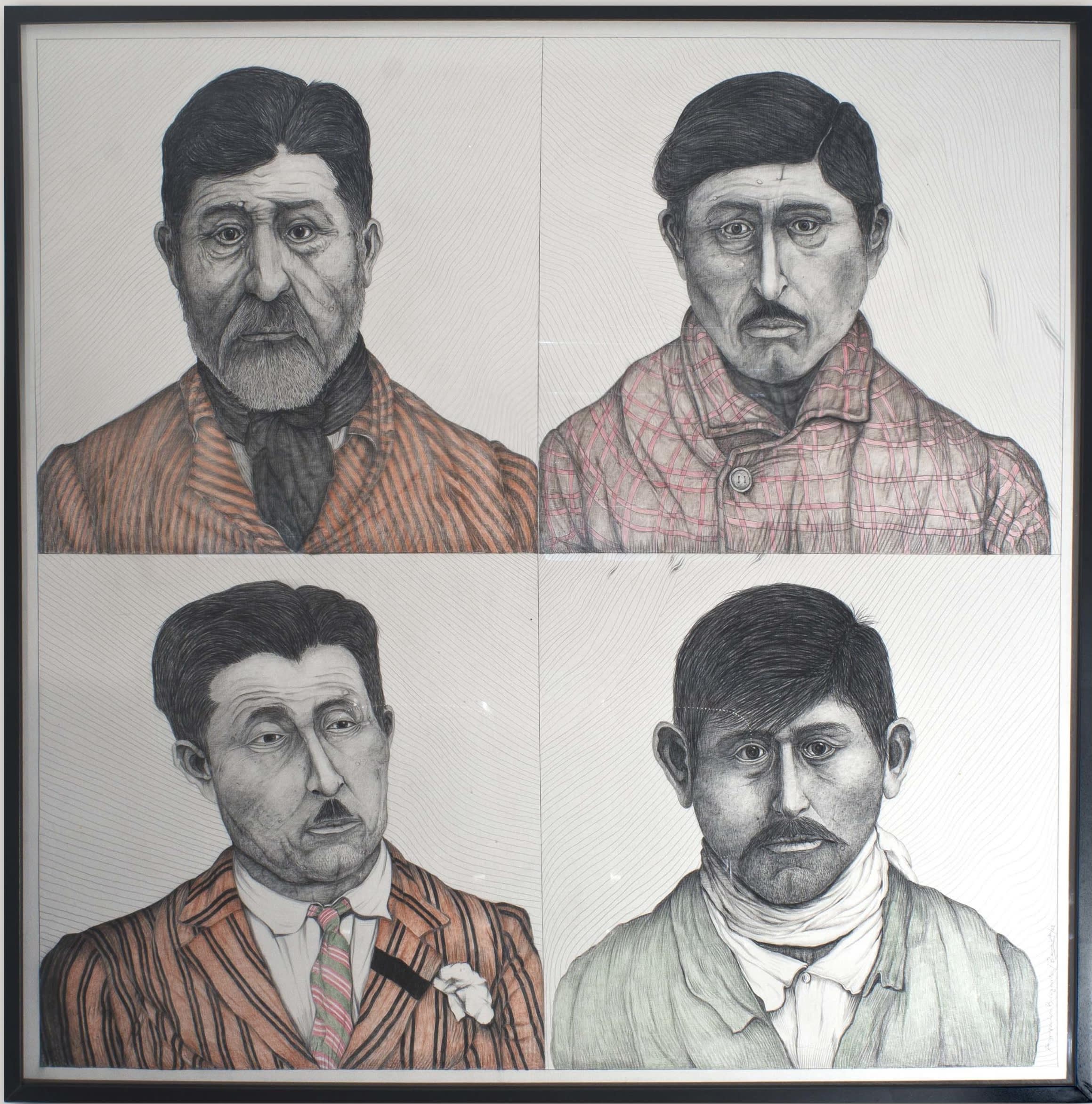

In Agrupación Baigorrita A (Cacique Zavala, 1915 - Modesto Colini, 1891 - Anastasio Fraga - Zenón Zavala) (2008), Luis F. Benedit recovers the physiognomy of four descendants of popular caciques who populated the Argentine pampas. With charcoal, graphite, sanguine, and a figuration close to that of police identikits, the artist gives faces to forgotten characters of history, to those who did not get to write it because they did not belong to the group of winners.

Luis Benedit "Agrupación Baigorrita A (Cacique Zavala, 1915 - Modesto Colini, 1891 - Anastacio Fraga - Zenón Zavala)", 2008

Anna Bella Geiger chooses a different strategy to approach the official images of native peoples. In her series, Brasil nativo, Brasil alienígena (1976-77), she starts with commercial postcards with photographs of aborigines of her country and reinterprets them using her own body and that of her friends as tools for critical inquiry. In the parodic reconstruction, in the absurd and artificial poses that copy those chosen to “represent” the ethnic richness of Brazil, the artist reveals the visual manipulation and ideological appropriation by the government when it comes to providing the country with an attractive and exotic diversity.

If it is a matter of counteracting the official images, the Serie de la realidad. Relevamientos. Ya no hay tiempo para elegir I (1979), by Elda Cerrato, offers a portrait diametrically opposed to the reality experienced in Argentina in those years when public demonstrations were forbidden. As was the case with Carlos Garaicoa's Puente Pearson, Cerrato resorts to art to reinstate this community experience, annulled by the government in power but latent in the memory and desires of the inhabitants. The human mass that grows both from the towns and from the cities shows a unity in the multiplicity founded on the need for an act of frank and full expression.

Something of this zeitgeist can also be perceived in the paintings of Guillermo Kuitca's series Nadie olvida nada (1982). In them, anonymous figures, women with their backs turned, desolate spaces, and empty beds, arouse open relations with the events that Argentina was going through at that time. The simple and schematic drawings invite the observer to immerse himself in them, in a movement of marked intimacy. The emotionality of these pieces is almost the opposite of the invigorating energy of Cerrato's crowds, although both find their origin in the same icy reality of the crimes of the military dictatorship.

In Renewal & Destruction. Walther PPK (2010), Colombian artist, Jerry Martin reproduces the revolver mentioned in the title by means of a typographic print of texts on paper. The weapon became famous for two very dissimilar references: for being the instrument with which Adolf Hitler committed suicide in 1945 and for being the pistol used by agent 007 in most of his original films.

Although Gabriel Valansi's photographs sometimes include somewhat cryptic references, it cannot be said that his images share Martin's ambivalence. The Argentine artist resorts to war records and evidence of weapons of mass destruction to highlight the belligerent irrationality of the world in which we live. In Díptico árboles. Wind, from the MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) series (2014-15), stills from a sequence of destruction are assembled in a lenticular support that offers different views of the event as the viewer moves in front of the piece. In Foto nuclear (2009-15), the image is printed on a glass plate that gives it an ambiguous and somewhat ominous luminosity. These effects contribute to the emotional impact on the public, to establish meaningful relationships of proximity with the observer, which function as a bridge to involve them reflexively in the political aspects that underlie the registers.

Finally, there are artists who prefer to approach history and social reality from the testimonies of its protagonists. Their work is usually based on extensive research processes that involve intense interpersonal ties and requires the development of forms of production and visibility of the social conflict that do not affect those involved. In these pieces, metaphors, metonymies, displacements, and the use of materials and objects that embody narratives in a veiled manner are common, although without sacrificing the emotional thickness that lies at the very heart of the testimonial story. They are pieces that appear to exhibit objects, but in reality, they expose people’s souls.

For the making of the Atrabilarios series (1992-2004), Colombian artist, Doris Salcedo obtained shoes that had belonged to women who had disappeared in different rural areas of her native country; she placed them in niches in a wall and covered them with a semitransparent fabric, sewn to the support with surgical thread. Here, the shoes are mute witnesses of a body that no longer required them. Charged with a fierce sensibility and dark connotations, they rest silent, unreachable, before the astonished gaze of the viewer.

Sin título (from the series Recados póstumos) (2006), by Teresa Margolles, a Mexican photographer, is no less bloody. It is the photographic record of an urban intervention carried out by the artist in the city of Guadalajara, where she reproduced phrases from suicide notes on the marquees of abandoned movie theaters. The harshness of the phrases almost exempts any critical comment. One of them reads, “Por la constante represión que recibo de mi familia. 19 años” [Because of the constant repression I receive from my family. 19 years old]. And another, “No me extrañen ni me lloren. Hagan de cuenta que me fui de viaje y volveré. 14 años” [Don't miss me or cry for me. Pretend I went on a trip and I'll be back. 14 years].

Even in the harshness of these phrases, or perhaps precisely because of the way in which a poetic operation brings them back to memory, sensibility, and thought, contemporary art manages to connect us with the most intimate fiber of our time.