A few days ago, the coach of the French national team, Dider Deschamps, gave a press conference in Qatar ahead of the final match. As he was answering questions, a journalist asked him if he thought Argentina's effusive fans were causing any kind of pressure. Deschamps thought for a second and replied: "I am aware that Argentina has enormous support and it is something valuable. They will have a strong presence of Argentine fans and others who sympathize with the team in the stadium and they will be noticed. They are passionate and will support their team to the death. They are also expressive and sing a lot. This will give a festive atmosphere to the World Cup final, but our rival will be on the pitch”. It never ceases to interest me when someone defines us as passionate, an adjective I'm more accustomed to using for ourselves than hearing from the mouths of others.

Just as the French coach predicted during the final, the stadium thundered with all kinds of chants cheering Lionel Messi's team. In the hardest stages of the match, when hope was fading, the fans, who carried painted drums, raised the volume of their voices, changing their songs to suit the moment, just like a rapporteur. After a stressful, exhausting and adrenaline-filled match, Argentina won and became world champions. The celebrations in Buenos Aires were long awaited. Fans jumped on the roofs of Metrobus stations, hung from traffic lights, and some even felt the need to climb to the top of the obelisk and hang from its windows. A fabric factory on Lavalle St. opened its second floor window and frantically cut flags to throw them to the partying crowd in the street, who euphorically received them, singing the national anthem.

It didn't take long for videos and news of celebrations around the world to pour in. In Sydney, a massive contingent of Argentines took over The Opera House and the celebrations got so out of control that the police asked them to leave. Chanting “We're not leaving, kick us out”, the police were greeted not with reluctance, but with hugs. The Argentine fans, jumping up and down, pulled the police into the mosh, and after a few minutes of confusion, they joined in the celebration. An Argentinean journalist said excitedly: "wherever we go, we are locals". This phrase resonated with me, and I think it only makes sense for a few nations. Because of our history, we Argentines are known for being globetrotters and/or expatriates. Expelled by the economy, by the constant abuse of a system of corruption that we are unable to decipher, many decide to “try their luck” with the passport inherited from that Italian or Spanish grandfather who came to the new continent with the same hope with which the young people are now leaving.

This explosion of Argentineness of the last few days brought back a memory, a story I like to recall from time to time when I feel I lose a few norths along the way. Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica (1937-1980) was one of the most important members of the artistic and political movement called Tropicalia (named after one of his works), and was recognized for his struggle for freedom, for not being pigeonholed into trends and for his constant rebellion against any kind of oppression, be it artistic or political. His beginnings were in 1950, with rather geometric works. Then, by 1960, he began with a series called Bolides, where these geometric forms take on three-dimensionality with elements appropriated from favelas. The architectural inspiration is manifest, plus Oiticica was a great dancer and liked to include movement in his pieces, on a mission to capture the spirit of his surroundings. By 1968, Brazil was plunged into a deep crisis and the de facto government suspended habeas corpus. The dictatorship was installed to mark one of the darkest moments in this nation's history, with mass arrests, torture, and people disappearing. Artists were targeted, prompting a large exodus from the community. Escaping from this regime, Oiticica traveled to London, where, fascinated by the freedom in the streets, he sought a space to exhibit his work. His goal was to create an installation that he described as an “environmental manifestation”.

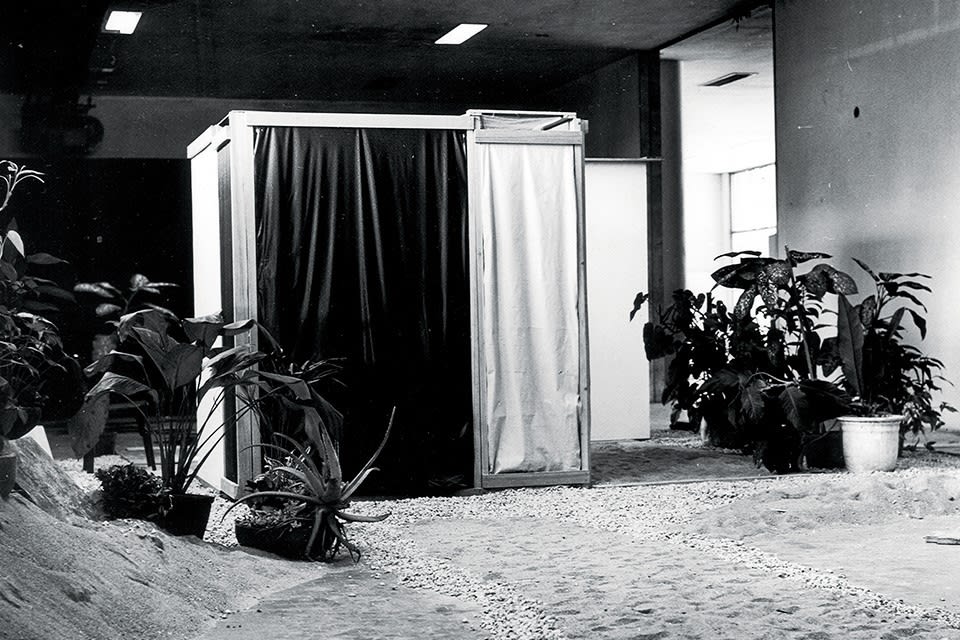

In 1969 the artist presented “The Whitechapel Experiment”, a completely disruptive exhibition where visitors were forced to immerse themselves in a sensory experience, which today can still be visited in various museums. The floor, covered by an important layer of sand, forced everyone who entered to take off their shoes, walk as if on a beach to go through an installation of plants, hay and a labyrinth of precarious fabrics and wood. In these spaces people could lie down to rest or to listen to the birds flying around them. The call for that exhibition was thunderous, large numbers of people came daily to immerse and relax in the experience, they brought books to read, they had meetings and talks, some mothers brought their children to play in the sand. "Tropicalia is nothing more than a map, a map of Rio. It's a map that you can get inside," the artist explained in London. This exhibition, key to understanding the cultural scenario of the time, not only represents one of the artist's best works, but was also his way of responding to the political situation in his country. Tropicalia is the banner that, no matter where we travel, no matter how far from home we are, no matter how many continents separate us from our homeland, it is an expression from which we cannot separate ourselves. Tropicalia is not only a feeling of nationality, it is a reality. It is to immerse oneself in a world that is no longer rooted to a land, but that travels to every place where Oiticica, and now Tropicalia, goes, as it is to feel Brazil under our sand-covered feet.

Watching the celebrations around the globe for the World Cup on December 18, 2022, is a thrilling sight. The world seems full of Argentines wearing their jerseys, waving flags, singing the anthem and hugging strangers with tears in their eyes, it is a moving spectacle in itself. On television, you can see hundreds of stories of expatriates gathering around the microphones of journalists, who watch in complete amazement at the expressions of jubilation, adrenaline and absolute happiness. This roar of celebrations, this passion that bursts our souls, it is our Tropicalia. It is that way of carrying our homeland in our hearts, wherever we are. It is what makes us Argentines (not better or worse, just Argentines) around the world. It is the reason why we are recognized. And even for the (few) Argentines who are not football fans, we find passion, euphoria, and dedication in many other popular events. In the matches of Juan Martin Del Potro, one of the most outstanding Argentine tennis players, unconditionally accompanied around the world by his compatriots. Or in the late 80s and early 90s, when artists like Charly García or Soda Stereo toured the world, driving their fans crazy, who would sing “En la ciudad de la furia” emptying the air from their lungs and transforming their shows into epic experiences. Or as in any nightclub where the Argentine Hernán Cattaneo, one of the best DJs in the world, performs his show, there will always be a group of Argentines to accompany him in each track with a flag.

A flag that transcends all politics or governments, that transforms us into our own heroes, as did Emiliano "Dibu" Martinez, the best goalkeeper of this World Cup and possibly in the history of Argentina, fueled with courage hand in hand with this team, whose desire to win is boosted when a rival's comments minimize the Argentine performance. His desire to prove that Argentina is not a lesser or worse team for being South American, a title that we carry with pride. El Dibu uses every mental and physical tool to enhance his talent and leave everything on the pitch, that expression that comes from football and we Argentines apply to life as a whole. Perhaps, from the outside, we appear to be exaggerated, but I know very few tourists who can resist the experience of going to La Bombonera when they visit Buenos Aires, to jump with the drums of “La 12”. Although for some people football is a mundane experience, for us sport, music, culture, and art are the things that unite us to our land. It is, for those of us who live in Argentina, that moment of peace in the rift, of union.

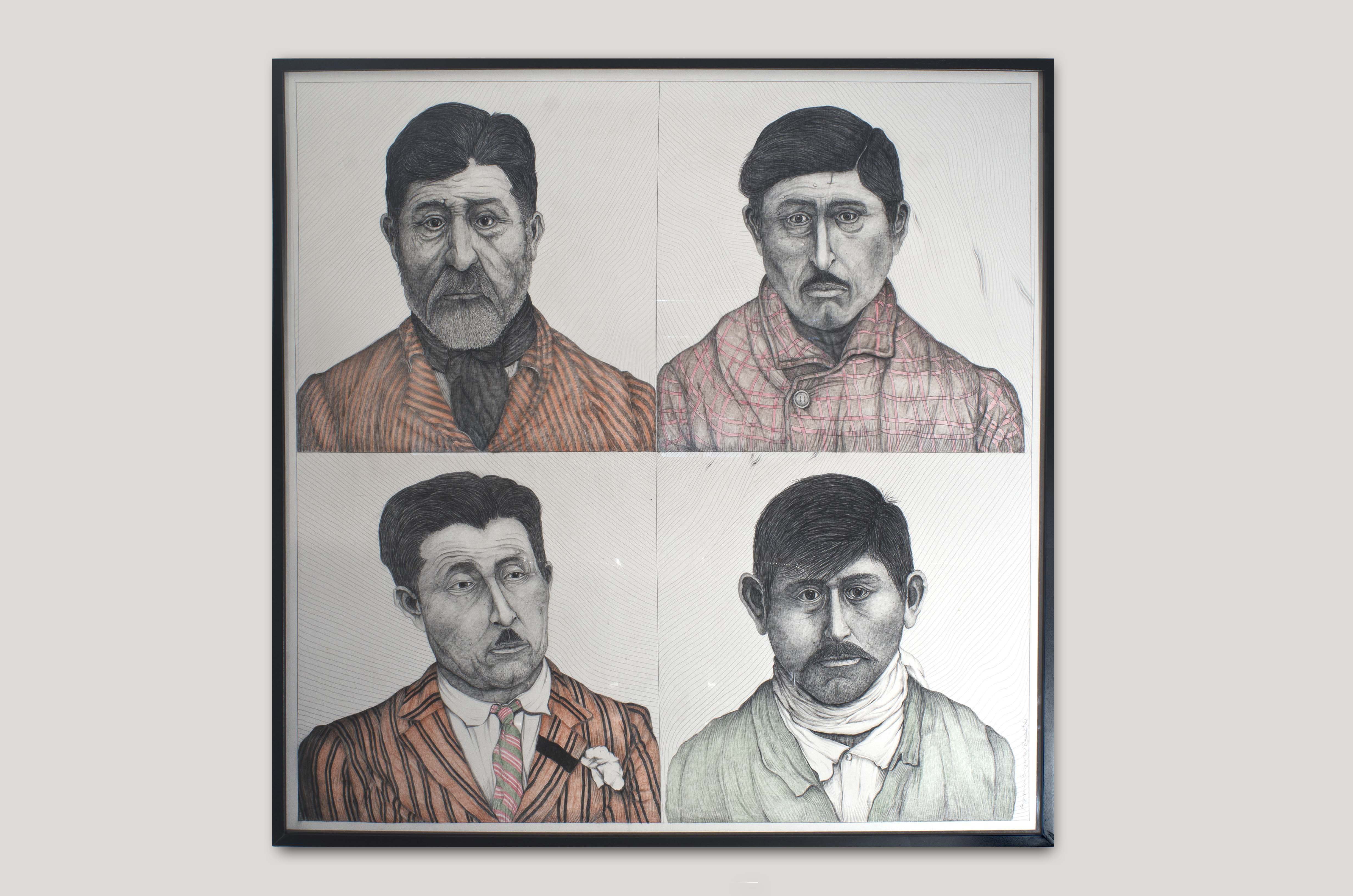

And for those abroad, it becomes that Tropicalia experience, where our identity can explode freely through the air in immeasurable demonstrations of love and pride. What we are, what defines us, is constantly at stake in popular expressions, and this World Cup is a confirmation that together we can still win even the toughest battle. The national team managed, at least for a few moments, to silence the hard arm wrestling of symbolic appropriation of the homeland, the identity and the nation that has been waged in our land since the creation of the Republic until today. A friction in the flesh of art for as long as we can remember, with artists such as Cristina Piffer with Patria, an installation consisting of a block of grease and kerosene with the word "patria" in the lower half, brushing against stainless steel. A constant reminder of the fragility of everything that word means, despite the decades we have spent building it. Or Agrupación Baigorrita A (Cacique Zavala, 1915 - Modesto Colini, 1891 - Anastacio Fraga - Zenón Zavala) by Luis Benedit, a work that has taken on new meanings especially in the last twenty years with the rural landowners' struggle to defend their crops and the constant tension between exports, working conditions and the insane taxes they are pressured to pay.

After the historic performance in the Argentina-Netherlands match, Dibu Martinez dedicates the long-suffering triumph to the Argentine people: “We played for 45 million. The country is not going through a good time economically and to give them a joy is the most satisfying thing I have at this moment”, he declares from the playing field between sweat and tears. With our hearts in our hands, we all traveled to Qatar for a second.

Football, music, friends, barbecue, art, our customs, and codes, cross continents and spread in the form of passion that makes us present, they carry our Argentine identity throughout the world, to the point of infecting it, like a pandemic that we exude through our pores. This is the art that we exercise as a tool of identity, our passion is our attachment blanket. Art is a fundamental piece of culture, the one that questions and refutes, affirms and raises, that there it is impossible for anyone or anything to take away from us what we really are, that politics and economy are circumstances, and both for those who stay to fight for it and for those who leave, that Argentina, ours, is not only incorruptible, but untouchable. It is a feeling so deep inside us that makes us local, wherever we are.

Argentina world champion!

December 19, 2022