One of the first things that caught my attention, when I personally toured the Balanz Collection of contemporary art, was a piece discordant with the times: a historical Raquel Forner from 1939 - the artist's most dramatic and existential period. Thinking about its relationship with the rest of the works, I tried to thread the curatorial idea behind the selection and noticed that it was a passionate and delirious collection, with works that were either intense and bloody or filled with love and lust that usher us into fictional narratives and fantastic worlds.

Just as the Cisneros Collection (Caracas and New York) has a large group of works destined to the concrete abstraction of the mid-twentieth century, with pieces of straight lines, pure colors and orthogonal visual fields, I would dare to point out that the Balanz Collection chooses the opposite: sensorial figuration or abstraction; organic, curved or diagonal lines; vibrant or even dirty color; the visual field in tension. Its works are not randomly acquired whims, but rather a complex corpus of contemporary art pieces that will be fundamental in the construction of the history of art to come. Although most of the collection is made up of works by Argentine artists, there is a rich dialogue and counterpoint in relation to certain key artists of Latin American and international art.

By "Spaces of Delirium" I refer both to the relationships between the works in the collection - which by being together are enhanced in the mind of the observer - and to the numerous works of "delirious" features that are part of this set. Delirium, as an alteration of the judgment of reality with certainty and conviction, as well as the persecutory mental automatism described in psychoanalysis, alludes to the repressed interior, which must be deciphered and interpreted as a dream because of the ambiguity of its message. Freud studied this theme at different times in relation to neurosis and psychosis. For example, in his analysis of The Rat Man, the word "delirium" appears in relation to the trance-like thought of the man who, due to morbid persecution, fears that his parents know his innermost thoughts[1]. It is around this concealed idea of vital feelings that stories are constructed in numerous works of the Balanz Collection, referring to neurosis and psychopathologies such as obsessions, paranoia and psychosis, as well as to dreams and creative fantasies, typical of the inner world of visual artists.

The word "space(s)" refers, in the first instance, to physical spaces where things happen, habitats and landscapes both earthly and surreal; secondly, to the plastic and visual space of the painting, sculpture or installation; and, thirdly, to the curatorial space: that in which the collection is thought of as a physical and mental journey that presents interstices for reflection and debate and even invites one to wander freely in their attempt to interpret it.

The work of Raquel Forner (Buenos Aires, 1902-1988), Los frutos (1939), is initially appealing due to its metaphysical-surrealist overtones; it is an image that plays at the boundaries of expressionist realism through the distortion of sizes and estrangement, in a brutal representation of the horrors of war[2]. At the same time, it is a work loaded with the political and humanitarian concerns of the artist herself, as a result of what is happening in her contemporary world. It belongs to the hinge year between the series dedicated to Spain: España (1937-1939) and El drama (1939-1946), both focused on the tragic and existential sufferings of war from her perspective as a woman.

This oil painting is composed of the synthetic and central figure of a burned tree: dry and dead, with short, truncated branches without foliage, which produces death as its fruit - human fragments hanging from its branches, symbolic testimonies of the massacre. Two hands pierced through the palms refer to the crucifixion of Christ[3], while a foot tied to the trunk (that doesn't touch the ground) and a woman's head, also torn and with its gaze fixed on a lost direction, speak to the loss of meaning in life.

In this work, it seems that the artist herself is the one who suffers. Perhaps, this is so because in Karl Koch's personality test, in the simplicity of the drawing of a tree, the representation of the structure of the artist's own "self" is captured. Antonio Berni, a contemporary of Forner, said about her in 1947:

The personality of this artist is an inexhaustible source of subjections, not only for what she tells us about the outside world but also for all that she is able to reflect of her rich individual psychology. Every detail of her work is an open door to meditation.[4]

It is a meditation on the destiny of the world and human existence, because "her work is the drama of the world; this drama is so present that all its expression is an anguished allegory of the drama itself"[5]. Berni also remarked: "She lives in moral exile"[6]. Forner herself saw it well, from her feminine point of view:

we women suffered in the rearguard more than men, because they had the battlefield to take revenge, while we remained powerless, making the pain even greater. I have painted only women and children because I am sure that they suffered more in their terrible stillness.[7]

Raquel Forner, porteña and daughter of Spaniards, did not experience the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War or the ravages of an expatriation, but she did feel them with empathy from her position as a woman, in a modern world connected by travels, letters and news, in which death and drama were a universal pathos. These ways of seeing the world, according to historian Paula Bertúa, "are political expressions that defined a discursive space of their own, where they offered other perspectives from which modernity could be understood and expressed."[8]

Although the war theme is classic, during the 1930s, the way of presenting it was through modern aesthetic resources of the time. Such is the case of Los frutos, through the fragmentation and estrangement of the distorted image of parts of an incomplete body, or that of Picasso's Gernica[9] (1937),where it is presented in a deconstructed form, with multiple perspectives on the same plane in the cubist manner, in a "wounded painting", according to the author himself, with whom Forner shared the concern for a Spain broken by horror.

These works "shape a pictorial atlas of the massacre, a psychically charged archive that has a lot to say about the trauma."[10] For Georges Didi-Huberman,

it is a bit as if, historically speaking, the trenches opened in Europe during the Great War had given rise, both in the aesthetic field and in the human sciences - we may recall Georg Simmel, Sigmund Freud, Aby Warburg, Marc Bloch -, to the decision to show by assemblage, that is to say by dislocations and recompositions of the whole. Assemblage would be a knowledge method and a formal procedure born of war, which takes note of the "disorder of the world".[11]

The debate, at that time, was the questioning of the representation of the current world, which, for the defenders of abstraction, could no longer be symbolized through figurative[12] work. Faced with this, Forner argued: "Every work of art is the result of an abstract conception,"[13] and emphasized:

What really counts is the plastic density, which gives the artist's message endurance over time and makes such a message a truth of the spirit that survives the aesthetic concepts, passions, ideals, and even the religion of the time that gave rise to it and from which, over the centuries, it will become a vital and irreplaceable testimony.[14]

In contemporary art, an artist who perhaps shares Forner's existential feeling in relation to death is Charly Nijensohn (Buenos Aires, 1966), represented in the Balanz Collection with a photograph from his series Dead Forest (2009), which is composed of the film Amazonia[15] and printed stills of the disaster caused by the Usina Hidrelétrica de Balbina (Babina Hydroelectric Dam).

Thirty years ago,

the Brazilian government

authorized the construction

of the Balbina Hydroelectric Dam,

in the heart of the Amazonia region,

with the purpose of providing energy

to the city of Manaus.

As a result of this development,

the largest artificial lake in Latin America was created,

flooding a substantial part of the Amazonia[16] forest

and forcing the movement of the Waimiri and Atroari

tribes from their

ancestral territories.[17], [18]

The construction of this dam between 1979 and 1989 was considered one of the worst ventures in the world, since, in addition to the damage it caused, it was not efficient. Built on a flat area, the dam divided the rainforest into 3546 islands, confining species, forcing fish and riparian animals to either adapt to the lake environment or die and forcing terrestrial species and humans to move to other areas. Due to the accumulation of sediment and contamination, the waters lost their transparency and purity, destroying the great biodiversity of the area.

In Nijensohn's photograph, with a palette reduced to neutral grays and black, we see a man standing on a floating raft, perhaps perplexed by the very strange landscape that surrounds him: a phantasmagoric scene, a shadowy dream, with the visibility thickened by the mist of an immense lagoon surrounded by numerous, standing tree trunks, totally bare, without branches or leaves, dead (like Forner's tree), destroyed by the flood. The film incorporates the sound of wildlife, the slow flow of two boats with two men sailing along, the slow passage of time with night and day scenes, a windy rain and thunder that breaks at an almost epiphanic moment. At first sight, the sublime beauty of the landscape is astonishing and, as we focus on the image, we begin to realize what really happened. Nijensohn manipulates reality and fiction in this incredible and delirious landscape scene that seems unreal but is a real cemetery of nature.

This work, in relation to its atrocious beauty, aligns with the concept of elegy, as proposed by the art critic and philosopher Arthur C. Danto:

What is an elegy? Danto was asked to answer: "An elegy is a poetic composition in which some painful or unfortunate fact or meaning is mourned. Elegies are visual meditations on death as a form of life. They are part music and part poetry, and their language and cadence are determined by the theme of death and loss. The elegy involves one of the greatest of human gestures: it is a way of responding artistically to what cannot be endured"[19].

In his work, Nijensohn reinforces this idea of timeless unreality and death by referring to the legend of the Flying Dutchman[20]: a ghost ship condemned to wander forever, aimlessly, not touching land until Judgment Day. Is this, perhaps, what could happen to us if we continue to attack the world? This artist's project is related to multiple energy developments and experiments in the area[21] and throughout the world, which resulted in ecological mega-disasters; as was the case at Chernobyl, in northern Ukraine, at the time the Soviet Union, after the accident that occurred there in 1986. Little is said today about the hundreds of similar nuclear bases scattered around the world. As a visual artist, Nijensohn reminds us of, and points out, this major problem. The means by which "civilization" tries to meet the increasing demand for energy, to the detriment of the ecosystem, should be replaced by the search for renewable energies, such as solar, wind, geothermal or biodynamic, among others.

Along with Forner and Nijensohn, Adrián Villar Rojas (Rosario, 1980) also shares the notion of existentiality: the ephemeral mysticism of our passing through the world, the vision of "the Anthropocene era". He is a "Renaissance" type of artist, with a trajectory of works of multiple dimensions, related to a post land art of monumental public art installations, in which he questions the historical and cultural actions of man in this world full of permanent ecological catastrophe.

The Balanz Collection owns part of one of his most spectacular works, both in terms of the image itself and it's colossal scale and production, composed of a series of simultaneous installations, executed with his team in different locations throughout 2017. It is The Theater of Disappearance, made on commission for the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden, the roof garden of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York, to which these pieces belong: the Kunsthaus Bregenz, in Austria; the NEON Foundation, in Athens; and The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), in Los Angeles. The project also includes a film trilogy of the same name.[22]

In this way, Villar Rojas deconstructs the concept of unity between artwork and art space, confronting and altering the normative functioning of each institution and connecting them as a "geopolitical-philosophical interaction."[23] The artist states about his work: "I see The Theater of Disappearance as a sort of deconstructive homage to Western art, as if I were mourning it, from Greece to the United States", and emphasizes that his intention is "to trace a panoramic view of the West as a human project."[24]

The terrace of the Met - the museum that has its own version of history - was turned into a bizarre and somewhat decadent "surreal party,"[25] with elements of kitsch and close to science fiction: the Met Costume Gala, an Alice-in-Wonderland-like mix of fantasy with an eccentric gala fundraising banquet, for which the museum is well known, in addition to its vast encyclopedic collection, its Cloisters and other replicas of the history of art and civilization. It is the world as a staging, as a mise-en-scène of characters and lifeless elements painted in black or white, finally complemented by the audience, immersed and sleepwalking between the different scenes, in which the simple disorder of "things"[26],[27], is part of a hidden plan, a larger fictional delirium.

Left: View of The Theater of Disappearance. Right: Head of a hippopotamus. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Amenhotep III (ca. 1390-1352 B.C.).

His work is site-specific, created amid a sensitive relationship with the institution where it is exhibited. Because of this way of working, Villar Rojas considers himself a nomadic artist, with a "parasite-like" work team (his own words), since, for each exhibition, the group settles and temporarily inhabits the institution or the space to be intervened. In this regard, Villar Rojas says: "Each museum-institution represented a very precise place for me to situate knowledge production and identity construction in coevolution with the cities and countries that host them [the exhibitions]."[28]

His things are tracings of the objects of history, not in a pedagogical mimetic sense but as a complex staging, composed of numerous parts and remnants of the millenary history of mankind on earth. His installations are only the visible tip of a process of research and production; they are an obsessive log of exploration records of the departments forgotten by the official history of the museum, they also question the way it functions in departmental hierarchies and exhibition codes:

The Theater of Disappearance creates a rupture that points to the fact that history is edited, that it is moved and positioned and repositioned by human hands - in this case those of Rojas and Galilee. Rojas shows that these works are imbued with a narrative that was chosen by curators and art historians, and the chaos - this scrambled encyclopedia of art - attempts to release them from the standard narrative we assign to art history. The sculptures look like they're finally breathing[29].

In the case of the Met's work, Villar Rojas worked in a complex process with his staff and a team of experts from Hollywood, through which they replicated more than 100 pieces, specially chosen from the collections, as well as 15 people (including a woman in her seventies and a five-month-old baby) using 3D scanners. These pieces were made of polyurethane foam, covered with black and white industrial matte paint, and also covered with a fake patina made of dust. In this way, one could appreciate "the effects arising from those imaginary theaters that are at the same time organic and post-human."[30]

In his works, Villar Rojas applies a variety of ways of thinking and constructing his installations. The artist does not choose his material at random, but rather gives special importance to the relationship between the organic and the inert, the relationship between the work and its surroundings, the passage of time, growth and/or decomposition, life cycles and the alchemy of the elements. This refers to Victor Grippo (Buenos Aires, 1936-2002), in works such as his series "Valijas", Anónimos or Vida, muerte y resurrección and, in the same vein, to Elba Bairon (La Paz, 1947), in her installation of depersonalized figures presented at Malba in 2013. Thus, in Villar Rojas' complex and enigmatic work, there could be references to numerous other artists, starting from El Bosco, with his representation of human destiny in the Garden of Earthly Delights; or a Robert Smithson, in his land art works; or Christo et Jean Claude and his colossal public interventions; Mattew Barney, given the strangeness of his staging and filmography; even a Rikir Tiravanija, in his horror vacui; and, of course, Guillermo Kuitca, as far as the theatrical imagery is concerned.

Wagner: El holandes errante, escenografía por Guillermo Kuitca, Teatro Colón, 2013

The idea of fictional delirium is also seen in Mondongo, an Argentine artist collective formed in 1999 by Juliana Laffitte (Buenos Aires, 1974), Manuel Mendanha (Buenos Aires, 1976) and Agustina Picasso (Buenos Aires, 1977), in their work Serie Roja no 3 (díptico, 2008)[31]. The collective's works are also characterized by the tension between matter and figurative image with a narrative sense: For this series, started in 2004 and composed of about 30 works, they used plasticine to tell a new version of the children's fable Little Red Riding Hood, in an "iconoclastic, punk, imaginatively inventive, sharply particular, personal, laid-back look at life - a 'do what you like' situation from a ground zero world loaded with elements from a grotesque farce."[32]

Narrative figuration in art dates back to the very beginning with cave paintings, while it is also very present in religious art, for example, in the Way of the Cross (painting in episodes), and in educational murals designed for illiterate audiences. It arrived in the twentieth century through comic strips, reinforced by artists such as Antonio Berni and others related to the School of Paris in the sixties.[33]

On the other hand, the use of material that escapes the most traditional in art also reminds us of works from the twentieth century, from the fifties and sixties, such as informalism, nouveau réalisme and the idea of the French bricoleur. This usage suggests a relationship with recycling and the re-signification of the material to reinforce a plastic image. Argentine artists, such as Alberto Greco or Keneth Kemble, used ignoble materials that could decompose and rot, just as Berni chose the materials that best represented the idea he wanted to express. In this way, he used metal sheets and scraps for the villa miseria in Juanito Laguna and trimmings and lace in the case of Ramona Montiel. In this same sense, the Mondongos choose the material[34] they believe to be most relevant to discuss different themes, such as intimacy, sexuality, marginalization, work, commerce, power and death.

Antonio Berni, Juanito bañandose entre latas, 1974.

The Mondongos, lovers and specialists in the history of cinema, grew up with the Pictures Generation group of artists as a model of international contemporary art, who, based on conceptual art, proposed a critical reinterpretation of popular culture images. Mondongo's work is close to the idea of Cindy Sherman, also interested in the narrative image in her photographs: "It seems to me that, in horror stories or fairy tales, the fascination with the morbid is also a way of preparing for the unthinkable."[35]

Once again, the mixture of fiction with the idea of cruel beauty appears to deal with themes that tie the intricate and morbid together, with the delicacy of the image and a meticulous work of the material. In this way, Mondongo links the image of the little red riding hood girl who "unintentionally" shows her crotch, which brings her closer, in diptych with the wolf, to being a "Lolita", through a relationship of psychoanalytical implications. This girl, careless of social norms in regards to modesty, recalls those portrayed by Robert Mapplethorpe in the seventies, and the ten-year-old girl taken by Richard Prince, Brooke Shields, in the photograph Spiritual America (1983) - works in which both artists carried out a subtle work between the beautiful and the pornographic.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Rosie, 1976, gelatina sobre plata, 35 x 35.5cm.

Richard Prince, Spiritual America

This relationship between material and delirious figurative narrative is also displayed by Marcelo Pombo (Buenos Aires, 1959), an artist represented with two works in the Balanz Collection, both untitled: a drawing representing a couple of men in a surreal landscape made with black marker (an ignoble[36] material), from 1995, and a painting in synthetic enamel on wood, from 1997. Alfredo Londaibere (Buenos Aires 1955-2017), also from the same circle of Buenos Aires artists, has an exquisite and fantastic landscape in the collection, in oil on board, untitled and undated, sharing this plastic and ideological interest in which the "indecent"[37] and the ornamental are strategies of rupture.

Both Pombo and Londaibere participated in the Grupo de Acción Gay (GAG) between 1983 and 1985, an experience of sexual activism, together with Jorge Gumier Maier[38]. The GAG was key in the early days of the group of artists known as the "Grupo del Rojas"[39], which alluded to the artists linked to the exhibitions and actions promoted by the Centro Cultural Rojas, curated by Gumier Maier between 1989 and 1997, and then by Londaibere until 2002. As Francisco Lemus points out:

By investigating the images - collages and drawings analogous to the visual culture of the counterculture - sketched by the GAG, its texts and different messages, we observe a display of signs around gay abjection and the camp codes that go beyond the merely identitarian, giving rise to a morality of the minority reactive to social conventions and critical of leftist ideals due to their heteronormative regulation.[40]

Those of the GAG were artistic productions that developed in the heat of the underground during the last years of the military government and the beginning of the democratic period. These artists were identified by Jorge López Anaya in the newspaper La Nación[41] under the term "light", and their work was also described under other pejorative terms such as "bright art", "pink art", "apolitical art", "queer art" and even described by Pierre Restany as "guarango art" (rude, in lunfardo). The GAG and its art were marginalized by the heteronormativity of the time, only to later be legitimized by the public, critics and art history[42].

Alberto Goldenstein, Retrato de Marcelo Pombo, 1992, Museo Castagnino MACRO

Marcelo Pombo was self-taught, a lover of handcrafts and trinkets. Along with many of the Argentine artists of this period, he shares the pleasure of working with ignoble materials such as cardboard, nylon and polystyrene, and the conjunction of references to both high art and popular art based on contemporary visual codes of popular culture, such as design and advertising, which he resignifies, bordering on kitsch, in a critical version of "good taste".

As for Londaibere, he did not have a professional university education either, but he defended his craft: Constantly working in his studio since 1974, he became very prolific. Driven by spirituality, the artist was interested in "minor" techniques and popular materials, in the search for the restitution of their sacredness. Curator Jimena Ferreiro argues that "Londaibere ended up making painting a personal religion and a daily procession."[43] In his paintings of radiant colors with counterpoints of balance in white, he achieved a climate of luminosity and harmony. He was interested in aesthetics, in being able to beautify everything. He said: "I would like my work to be shown, contemplated and enjoyed."[44]

Alberto Goldenstein, Retrato de Alfredo Londaibere, 1988

The interest in aesthetics was something shared by the group; Inés Katzenstein defines it in relation to gender politics:

the artists of this paradigm aspired to create a beautiful work, outside of any formula of ideas, capable of leaving everyone speechless. In this context, the hyper-decorative, laborious and kitsch tendency of gay artists became a form of protagonism as part of a phenomenon of 'gay dispersion', through which the aesthetics of a minority group dominated the field.[45]

Such works were excluded from the artistic canon because of their dual degrading affiliation: on the one hand, with craftsmanship and, on the other, with what was understood as "feminine"[46]. This negotiation between high art and certain forms of everyday culture was one of the characteristics of postmodernism[47].

Although both Pombo and Londaibere resort to landscapes in their works, a classic theme in painting, they do so with reminiscences of surrealism in the fantastic and dreamlike nature of their works, perhaps as forms of mental escape, images of the intimate, of a personal metamorphosis and liberation with respect to the taboos of a world hostile to the gay community - all this at a time when HIV and AIDS, still in direct association, were synonymous with death. The critic Santiago García Navarro also thought of it from the artist's internal point of view, albeit in a crude way, which clearly shows a degree of self-referentiality in its poeticism:

Marcelo Pombo, the most characteristic artist of the group promoted by Gumier Maier, is the result of a series of personal micro revolutions. (...) Fragility as the delicate power of the puto, the obsession of good workmanship in contrast with the insignificance of the subject or the value of the object as an expression of the will to transform pure opacity into pure life, foolishness manifested no longer as stupidity but as another regime and another rhythm of thought (resulting from the crossing with the slowness, the hypersensitivity, the hyper-affectivity of the mentally handicapped who serves Pombo as an operative model): there are three lessons that the work left in front of those who wanted to take them on.[48]

In his painting, both in that of the Balanz Collection and in general, Pombo uses a precious, laborious technique, with a great profusion of details, which is done by dripping synthetic enamel in bright colors of pastel tones. Pombo himself, in relation to a work from the same series as the painting in this collection, said:

"The theme is like the quintessence of all the work I have been developing over the years. The poor and local simplicity associated with luxury, visual voluptuousness, evasion and fantasy."[49]

Pombo admired not only the landscape but also the history of landscape painting, which is clearly seen in the enamel. In his work, which emphasizes the horizontality of the humid pampa, with a gradient sky ranging from blues to intense light blue and an earthy post-harvest soil, a large unthreshed grain can be seen on one side, which seems to replace the hay of the historical paintings of Claude Monet and, especially, of Martin Malharro, with end-of-holiday confetti. Like Monet and Malharro, Pombo tried out "emotive variations of color on the same [austere] motif"[50]. In turn, this painting has, on its right, a strange street sign, which perhaps alludes to Berni, who, in addition to sharing Pombo's taste for ignoble materials and the horizontal landscape theme, included this type of sign as unusual, strange and delirious references to pampean roads and shantytowns[51].

Claude Monet, Meules, fin de l'ete, Giverny, 1891, óleo/tela, 60.5x100.5 cm., Musée d'Orsay, París

Martín Malharro, Las parvas (la pampa de hoy), 1911, óleo s/tela, 67x88 cm., MNBA, Buenos Aires

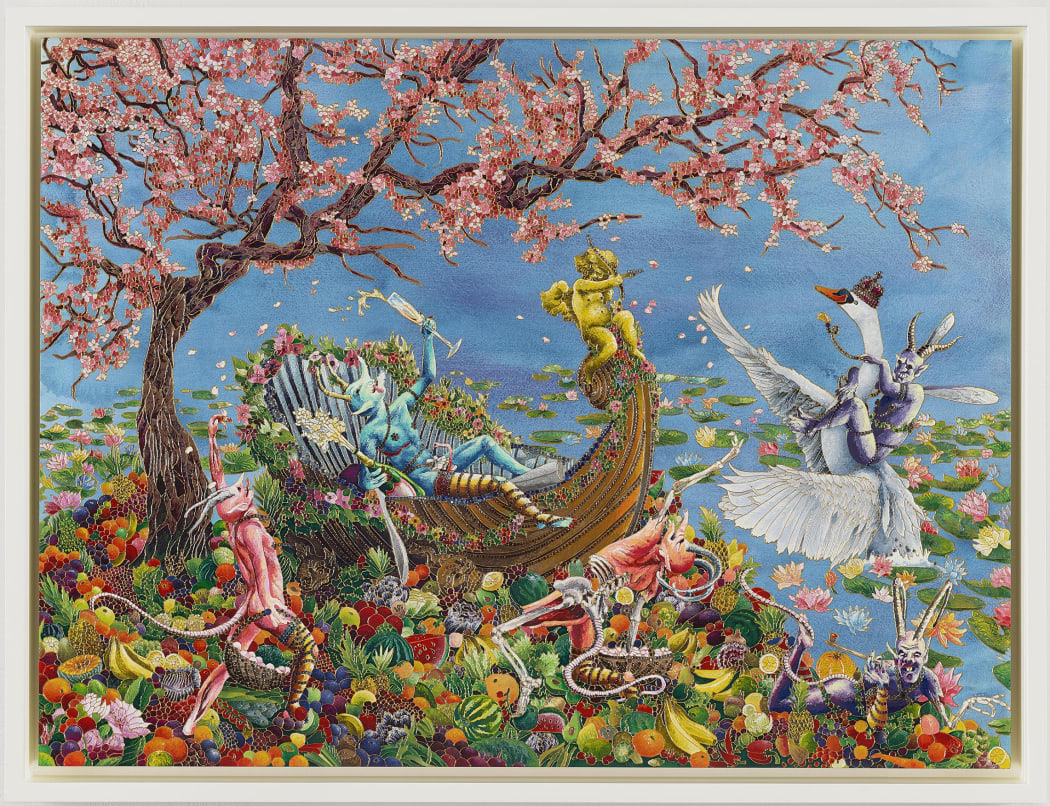

To close this saga of "places of delirium", or to further expose it to other fantasies and multiple interpretations of the works in the Balanz Collection, I am interested in highlighting Raqib Shaw (Calcutta, India, 1974). The artist, currently living in London, makes paintings about a delirious and fantastic world that uses beauty to mask its strong sexual content.

Sala de bonsai en taller de Raqib Shaw

Raqib Shaw developed a personal painting technique[52], close to cloisonné, with industrial synthetic enamel, and used an antique machine to create the different shades of color himself. He applies the enamel by hand, using special syringe-like tip droppers and, for finer details, he uses porcupine hair, which is even more fragile than the tip of a needle. To further enhance the sumptuous beauty, as in a marquetry, he inlays crystals that embellish and - at the same time - signify, by their brilliance and jewel-like value. But Raqib Shaw's obsession begins with the exquisite line drawing in pencil, which he composes by reinventing works of art that he admires for their perfection, such as those he sees in the National Gallery in London, or belonging to the ancestral oriental art and culture present in bonsai, botanical gardens, uchikake kimonos (reserved for weddings), traditional Kashmir shawls or Persian miniatures, among others. For Shaw, art and life are intimately related: connected.

Shaw's work in the Balanz Collection, Ludwig fantasy suite.... drunk on the wine of the beloved, 2018, done with acrylic eyeliner, enamel, watercolor and stones on paper on board, would appear to be inspired by the shōjo manga Ludwig Fantasy, which is part of the Ludwig Kakumei or Ludwig Revolution saga (still open-ended),[53] by renowned mangaka Kaori Yuki (Tokyo). The Ludwig fantasy itself was inspired by various folk tales such as Andersen's Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty and The Tale of Princess Kaguya. It is a comic strip with black humor and gothic horror undertones of the adventures of (anti) Prince Ludwig - egocentric, eccentric, narcissistic and sadistic - who, forced by his father to look for his future wife, travels the seas together with his valet Wilheim.

Tapa de Karo Yuki, Ludwig fantasy

Raqib Shaw's painting depicts various hybrid characters, gleeful monsters in a kind of orgiastic feast of lost paradise: one of them riding a symbolic swan, another pouring champagne, another smoking a long pipe, others dancing with a ritualistic atmosphere. The setting is marvelous and Japanese garden-like, with a cherry blossom tree in bloom, the most exquisite tropical fruits covering the ground and lotus blossoms suspended in a lagoon melting into the cerulean blue early summer sky. Again, obsessive delirium is presented under the guise of beauty.

[1] Freud, S. (1909). "A propósito de un caso de neurosis obsesiva. El hombre de las ratas", in Obras Completas. Amorrortu, Buenos Aires.

[2] In this line, see the work by Francisco Goitía, Paisaje de Zacatecas con ahorcados, II (ca. 1914). Colección Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, México, on the Revolution.

[3] Siracusano refers to Burucúa and Malosetti regarding "classical myths and Christian images of pain". See: Siracusano, Gabriela. (1999). "Lecturas y propuestas de Raquel Forner", in Burucúa, José Emilio (volume director): Nueva Historia Argentina. Arte, sociedad y política, Vol. II, Ed. Sudamericana, Buenos Aires, p. 45.

[4] Berni, A. (1947). "Raquel Forner". Ars Vol. 5, No. 32. 774879. Archivo Berni. Copia en Fundación Espigas (materiales especiales, carpetas Archivo Berni), Buenos Aires.

[5] Ibídem

[6] Berni shared with Forner the identification and solidarity with what was happening in the world, he was also involved in the struggles of the Popular Front (Anti-Fascist International).

[7] Raquel Forner in Amorim, E. (9 de octubre, 1946). Raquel Forner in Florida. Orientación, s/p. In Bertúa, P. (2012). Entre lo cotidiano y la revolución. Intervenciones estéticas y políticas de mujeres en la cultura argentina (1930-1950). PhD thesis (Universidad de Buenos Aires), pág. 225. Available at: http://repositorio.filo.uba.ar/bitstream/handle/filodigital/6125/uba_ffyl_t_2012_883904.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Last accessed: 07/2021)

[8]In Bertúa, P. (2012). Entre lo cotidiano (…). PhD thesis (UBA), pág. 11. Available at: http://repositorio.filo.uba.ar/bitstream/handle/filodigital/6125/uba_ffyl_t_2012_883904.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[9] Guernica was exhibited at the II Biennial of Sao Paulo (1953), as a symbol of modern art. It was the context for controversy and various interpretations of the work. According to Francisco Alambert, "its influence declined due to the desire for autonomy and the creation of an artistic vanguard, both Brazilian and international at the same time, starting from abstract-constructive approaches (neo-concretism) and only after the military dictatorship in 1964 will it be rediscovered as an icon by the artists of the "New Figuration". In Giunta, A. (ed.). (2009). "Goya vengador en el Tercer Mundo: Picasso y el Guernica en Brasil", in Guernica y el poder de las imágenes, págs. 57-79. Ed. Biblos, Buenos Aires.

[10] Paula Bertúa refers in her thesis to Aby Warburg and his Atlas of Memory, Mnemosyne, started in the 1920s. Bertúa, P. (2012). Entre lo cotidiano (…). PhD thesis (UBA), pág. 218.

[11] Didi-Huberman, G. (2008). Cuando las imágenes toman posición. El ojo de la historia 1 (Trad. Inés Bértolo), págs. 97-98. Machado Libros, Madrid. En Bertúa, P. (2012) Entre lo cotidiano (…). PhD thesis (UBA), pág. 221.

[12] Debate on the relationship between art, life and politics of so-called "pure art" versus "art in the service of society"; or between "art for art's sake" and "committed art". See: Wechsler, D. B. (2020). Mujeres del mundo. Estudios Curatoriales, 1(10). Available at: https://revistas.untref.edu.ar/index.php/rec/article/view/814 (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[13] Fuentes, E. y Neri, F. (1956). "Dos reportajes: ¿Figuración? ¿Abstracción?". [Article on Raquel Forner]. Lyra. V.14, No. 152-157 (1956). ICAA record 819310.

[14] Ibídem

[15] Nijensohn, C. (2009). Amazonia. [Film]. With a duration of 7:06 minutes, this project was the result of a collaboration between several artists and specialists on the subject, directed by Nijensohn in collaboration with Edu Abad, Teresa Pereda, Juan Fabio Ferlat and audio post-production by Edgardo Rudnisky.

[16] The surface area is between 2360 km2 and 2928 km2. On this subject, see: https://ejatlas.org/conflict/balbina-hydroelectric-dam-amazonas-brazil (Las accessed: 07/2021).

[17] Own translation

[18] Nijensohn, C. (2009). Amazonia / Dead Forest . [Film y text]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=94fvxIHmpRc (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[19] Guash, A. M. (2008). "La belleza entre lo político, lo ético y lo cultural. El retorno de la belleza según Arthur C. Danto". Materia Revista d´Art, nº 6-7, Departamento de Historia del Arte. Número monográfico. Iconografies, pp. 327-344. Available at: https://annamariaguasch.com/pdf/publications/MATERIA.pdf (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[20] The artist Guillermo Kuitca created the scenography for the version of Wagner presented at the Teatro Colón in 2013.

[21] From the same period is also the construction of the BR-174 highway, which forever disrupted the life of the Waimiri Atroari community ( self-named Kinja), who lived in isolation and suffered from western diseases and violence exercised by the military. Another similar case was that of the Yanomami, pointed out and documented in photographic and filmic works by the Brazilian artist Claudia Andujar since the early seventies.

[22] Film produced by Rei Cine, 1h 58'37'' long, presented at the Berlin International Film Festival, 2017.

[23] Phaidon.com (February 25 th, 2020). In Conversation: Adrían Villar Rojas and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Artspace. Available at: https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/book_report/in-conversation-adrian-villar-rojas-and-hans-ulrich-obrist-56474 (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[24] Íbídem. Op. cit.: "I see The Theatre of Disappearance as a sort of deconstructive homage to Western art, as if I were mourning it from Greece to the United States". "(…) the intention to trace a panoramic view of the West as a human project".

[25] Modabber, A. (13 de julio, 2017). Finding the Met in The Theatre of disappearance's Surreal Party. Met Museam. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2017/met-collection-in-adrian-villar-rojas-theater-of-disappearance (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[26] Engadin Art Talks (EAT). [Engadin Art Talks]. (February 12 th, 2018). Engadin Art Talks | Adrián Villar Rojas. [Video]. Youtube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5GXN9tXbOGY&t=146s (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[27] The artist mentions that he prefers to call his sculptures "things", which refers directly to Rubén Santantonín, who preferred to use the same word, in a personal theory about artistic creation. For Santantonín, the "thing" is the "antithesis of the object". In this regard, he pointed out: "(...) [the object] surrounds (...) man from that cold and fatal solitude (...). I understand 'things' as full, conceived by man in his interiority or penetrated by man in his exteriority (...)[,] they live thanks to man's imagination, I would say thanks to his poetry. If all human beings were to die, only objects would remain". (In Herrera, M. J., "Las cosas de Rubén Santantonín". Available at: https://www.malba.org.ar/las-cosas-de-ruben-santantonin/ [Last accessed: 07/2021]).

[28] Phaidon.com. (February 25th, 2020). In Conversation: Adrían Villar Rojas and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Artspace. Op. cit.: "(…) for me to situate knowledge production and identity construction in coevolution with the cities and countries that host them". Disponible en https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/book_report/in-conversation-adrian-villar-rojas-and-hans-ulrich-obrist-56474 (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[29] Modabber, A. (July 3rd, 2017). Finding the Met in The Theatre of disappearance's Surreal Party. Met Museam. Op. cit.: "The Theater of Disappearance creates a rupture that points to the fact that history is edited, that it is moved and positioned and repositioned by human hands - in this case those of Rojas and Galilee. Rojas shows that these works are imbued with a narrative that was chosen by curators and art historians, and the chaos - this scrambled encyclopedia of art - attempts to release them from the standard narrative we assign to art history. The sculptures look like they're finally breathing". Disponible en: https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2017/met-collection-in-adrian-villar-rojas-theater-of-disappearance (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[30] San Martín, F. (2017). "Adrián Villar Rojas, Metropolitan Museum of Art". Art Nexus No. 106, 2017, pág. 70. Op. cit.: "the effects arising from those imaginary theaters that are at the same time organic and post-human".

[31] Eduardo Costantini (son), at that time married to Agustina Picasso, and Camila Costantini, daughter of both, collaborated in this series. They were photographically portrayed in the Japanese Garden of the City of Buenos Aires, posing as Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf. After this series, Agustina Picasso moved to the United States and never again participated in the Mondongo society.

[32] Thread/Bare (exhibition). (n.d.). Mondongo: thread/bare. Press release. Op. cit.: "iconoclastic, punk, imaginatively inventive, sharply particular, personal, laid-back look at life-a "do what you like" situation from a ground zero world loaded with elements from a grotesque farce". Available at http://www.archive.track16.com/exhibitions/mondongo/index.html (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[33] From the term nouvelle figuration, coined in 1961 by Michel Ragon, new alternatives and divergences in relation to pop art emerged in debates and exhibitions that brought together numerous artists and works, such as Mytologies Quotidiennes (1964), Figuration narrative dans l'art contemporain (1965) and Le monde en question (1967), organized by Gérald Gassiot-Talabot in Paris; as well as the exhibitions of the Nouveaux Realistes group, organized by Pierre Restany; and those organized by Ceres Franco and Jean Boghici, Opiniao 65 and Opiniao 66 in Rio de Janeiro. Also, in relation to the Argentine New Figuration group, active between 1961 and 1965. On this subject, see: Ramírez, M. C.: "Juanito y Ramona en París, ¿mitos cotidianos o íconos del tercer mundo?", in Juanito y Ramona, pp. 83-103. MFAH and Malba, Buenos Aires.

[34] They used plasticine and colored mirrors to represent children's fables; cheeses and sausages for portraits, such as the one of Lucian Freud (2002) (also Balanz Collection); in addition to cotton and "glow" threads, coins and various materials, generally on wooden panels.

[35] "In horror stories or in fairy tales, the fascination with the morbid is also, at least for me, a way to prepare for the unthinkable", Cindy Sherman en Noriku Fuku (junio, 1997), "A Woman of Parts". Art in America, 85, 6: 74-81.

[36] This interest in handicrafts, neighborhood bookstore materials and children's imaginary was rescued in Ricardo Martin-Crosa's text "Escuelismo", published in 1978 in the Artemúltiple gallery, which linked the art of this generation with a "rhetoric of Argentine primary education", which years later was the inspiration for the homonymous exhibition and catalog, curated by Marcelo E. Pacheco at Malba, in 2009.

[37]Lemus, F. (enero-julio, 2015). ¡Arte light, arte rosa, arte marica! Reapropiaciones poéticas en el arte argentino de los años noventa como formas de resistencia. Revista Cambia, 1(1):117-132. Ver también el debate realizado en Malba, 2002, en texto homónimo en AA.VV. "Arte rosa light y arte Rosa Luxemburgo". Ramona. 2003, no 33, pág. 52-91.

[38] Gumier Maier (Buenos Aires, 1953) was also a journalist, with sharp texts published in magazines such as Sodoma, Fin de Siglo, Cerdos & Peces, El Porteño, among others.

[39] Other artists include Omar Schirilo, Alberto Goldenstein, Feliciano Centurión, Miguel Harte, Alfredo Kacero, plus others of trajectory such as Roberto Jacoby, Pablo Suárez, and women artists such as Liliana Maresca, Cristina Schiavi, Elba Bairon, Adriana Pastorini, among others.

[40] Lemus, F. (2019). Guarangos y soñadores. La galería del Rojas en los años noventa. PhD thesis, (UNTRF). Pag. 8. Unpublished, Buenos Aires.

[41] López Anaya, J. (August 1st, 1992). "El absurdo y la ficción en una notable muestra". La Nación.

[42] Among others, Elena Oliveras interpreted the works of this group as "ethics of the proximate". See: Asociación Argentina de Críticos de Arte y Telecom (1995). Historia crítica del arte argentino. Buenos Aires.

[43] Telam. (September 27th, 2019). "La pintura como una religión, desde la óptica de Alfredo Londaibere". Telam. Available at: https://www.telam.com.ar/notas/201909/395604-la-pintura-como-una-religion-desde-la-optica-de-alfredo-londaibere.html (Last accessed: 07/2021)

[44] Londaibere, A. in Luciano Pichilli. [UBA WebTv]. (S.f.). Londaibere. [Short-film]. Available at http://webtv.uba.ar/contenido/943/londaibere.html (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[45] Katzenstein, I. (2007). "Líneas y contrapuntos de una colección en proceso", in Pacheco M, Katzenstein I,y García Navarro S: Arte Contemporáneo. Donaciones y adquisiciones Malba Fundación Costantini. Buenos Aires, págs. 44-45. Quoting Olivier Debroise: "La dispersión de lo gay", May 1990.

[46] Lemus, F. (enero-julio, 2015). ¡Arte light, arte rosa, arte marica! Reapropiaciones poéticas en el arte argentino de los años noventa como formas de resistencia. Revista Cambia, 1(1):117-132.

[47] Huyssen, A. - FCE. (2002). En busca del futuro perdido. Cultura y memoria en tiempos de globalización. México.

[48]García Navarro, S. (2007) "Crítica a la política del campo" en Pacheco M, Katzenstein I, y García Navarro S: Arte Contemporáneo. Donaciones y adquisiciones Malba Fundación Costantini. Buenos Aires, págs. 36/37.

[49] Pacheco, M. et. al. (2007). Abstract de la pintura de Marcelo Pombo Rancho flotante (2006). In Arte Contemporáneo. Donaciones y Adquisiciones. Malba, Fundación Costantini, Buenos Aires.

[50] Laura Malosetti Costa says this in relation to Malharro, who carried out these tests on more than thirty canvases. See: Malosetti Costa, L. "Estilo y política en Martín Malharro". Available at: https://rephip.unr.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/2133/13167/separata-13---2008-3-12.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (Las accessed: 07/2021).

[51] See works such as Juanito Laguna entre latas (1974), Camino bajo los faros (1975), Atardecer en el camino.

[52] To know more about his technique, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bi7roXhkv0Y (Last accessed: 07/2021).

[53] Juki, Kaiori. Ludwig Kakumei: 1st ed. June 18, 2004, pre-publication December 16, 1998, Ed. Hakusensha, 4 volumes; Ludwig Revolution: 1st ed. September 19, 2007, Ed. Tonkam, 4 volumes; Ludwig Gensôkyoku, 1st ed. October 18, 2013, pre-publication December 26, 2011, Ed. Hakusensha, 1 volume; Ludwig Fantasy, 1st ed. November 12, 2014, Ed. Tonkam, 1 volume.