Sixty-five million years ago, the last dinosaur became extinct. The fall of a huge meteorite plagued the sky with millimetric particles. Although some theories speculate that the radioactive fallout may have been the determining factor in wiping out almost half of the species that populated the planet, it is certain that the absence of the sun's rays and the expansion of greenhouse gases were the triggers for the deadly change.

When has a species ever been affected in such a short period of time, as was the case with the latest SARS-CoV-2 viral spread? Was it during the end of the Cretaceous period due to the lethal impact of the asteroid? At what point did humans became involved in a single phenomenon in such a short period of time? The political and economic vicissitudes that accompany climate change had been predicting for decades a very acute socio-environmental crisis, but who could have imagined that barely a hundred years after the Paris Conference, the first global event in history[1], the year 2019 would mark not only the end of a decade, but also–perhaps–of an epoch.

Facing a panorama that had everything (or nothing) to do with any perspective of the future invented by fiction or imagined by surrealism, at the end of 2019 an unknown virus began to circulate through the air, adhering to human skin and to every terrestrial surface. Indeed, in a few months, individuals, families, cities, countries, and continents became isolated. Not even the Afrofuturist Octavia Butler in her saga of parables[4], in which decades ago she terrifyingly projected a future of walled neighborhoods and evangelical presidents, ventured to make deadly microorganisms fly through devastated cities. The shock of 2019 with the economies of the world paralyzed, while security forces controlled the circulation in the cities, found us in a state of unprecedented social atomization, thanks, paradoxically, to the brutal interdependence generated by capitalism.

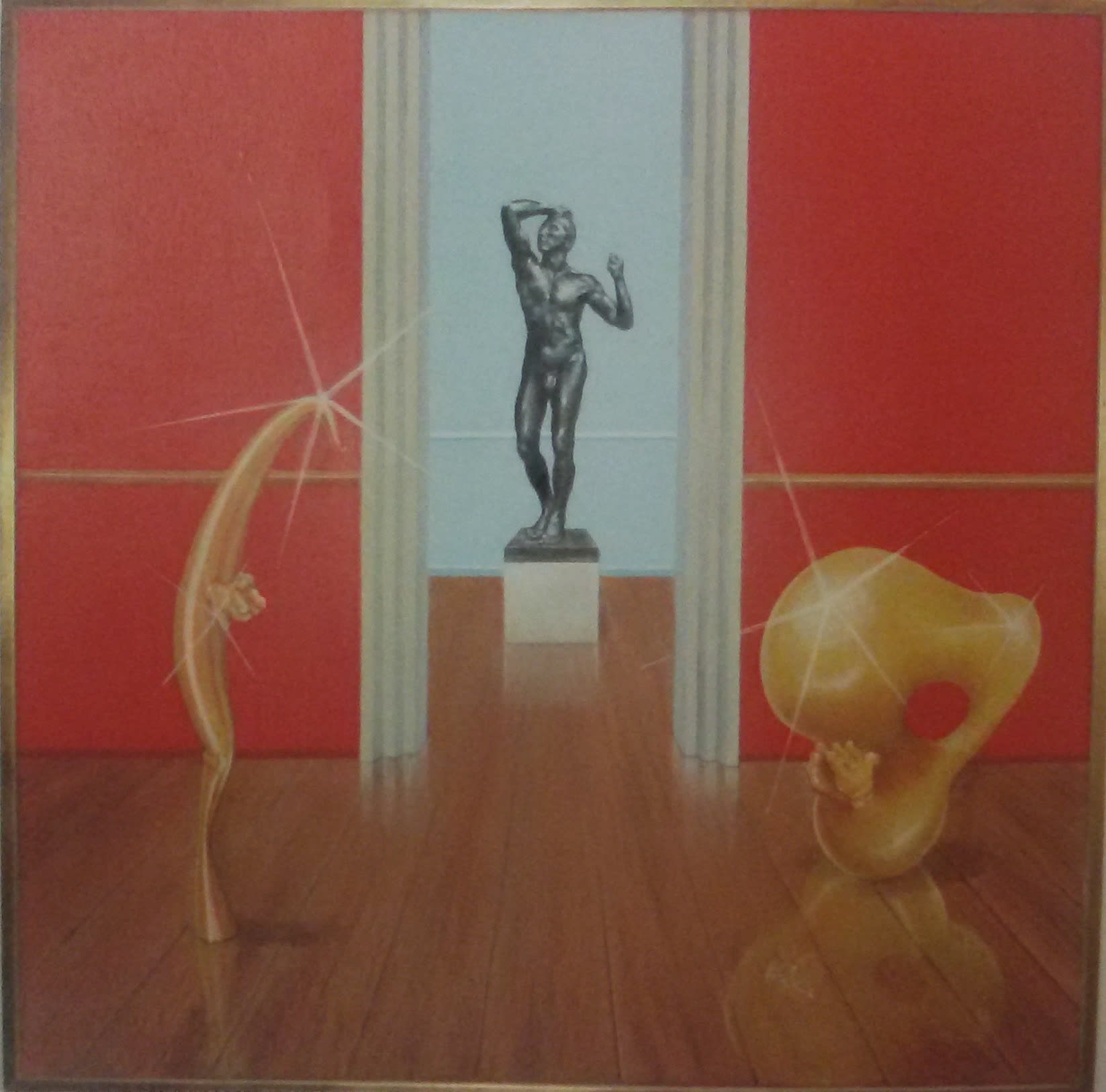

We are falling into the landfill, we are transforming the planet into an unhinged garbage dump, Michael Marder tells us.[5] And that sensation of free fall is what Sebastián Gordín represented, around 2011, in Días sin episodios 16318. In this work, furniture, paintings and a still lit light rail mysteriously sink in a scene part of the series of models in which the artist encapsulated forever small catastrophes that take place in libraries and museums, the favorite archives of knowledge.

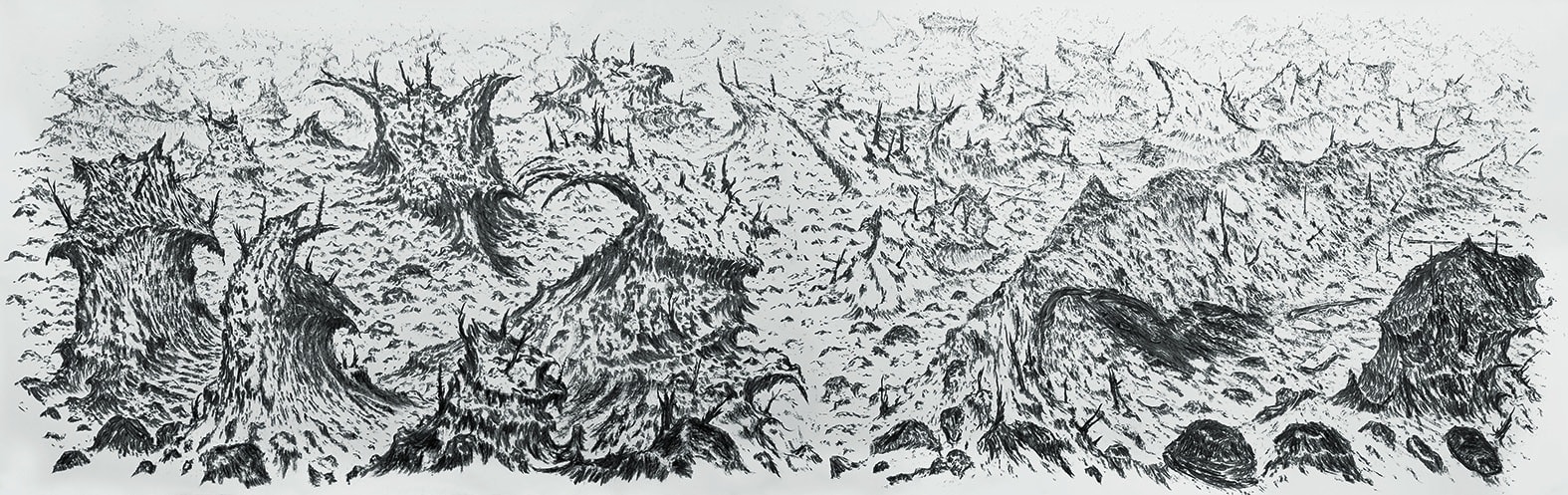

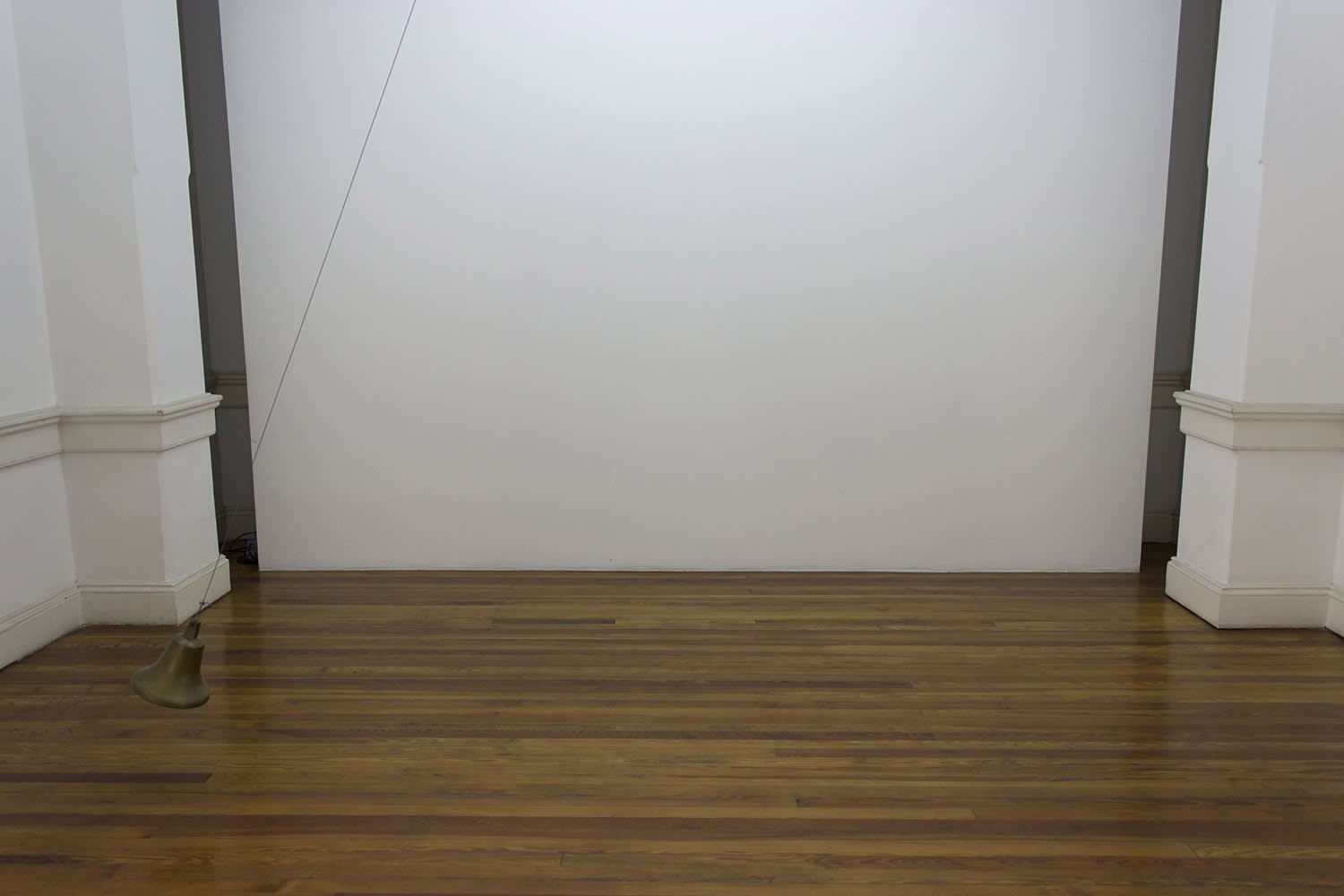

Some time ago, Charly Nijensohn, far from fantasy and surreal metaphysics, produced Dead forest # 8, an ambitious project where he recorded in video and photography the state of an enormous piece of land in the Amazon jungle transformed into a hydroelectric dam to supply electricity to Manaus. Not only were almost two thousand four hundred kilometers of nature destroyed, but the Waimiri-Atroari were displaced in pursuit of the construction of the artificial lake. Away from the figurative narrative, also in 2009, Eduardo Basualdo gave shape to La perla and La voz, two sculptures made of copper wire, a material used to make most cables, as it is an excellent conductor. Of magmatic or hydrothermal origin, this metal is extracted from the Pacific Ring of Fire, China and Russia. It is estimated that if it were to be extracted in the same way in Argentina, the income from mining exports by 2030 could be three times higher[6]. These double-sided pieces, due to the presence of the material in its raw state and the abstract form of the figures, have the power to transport us to the realm of fantasy and simultaneously alert us to the possibilities and consequences of the massive exploitation of this metal.

Realistic and fantastic, Nijensohn and Basualdo produced their works in the same year that Andreas Malm introduced the term capitalocene. Also by this time, in Australia, the worst bushfire had been recorded after the thermometers marked the highest temperature in its history. Coincidentally, a few days before this ecological disaster, Bitcoin, the cryptocurrency that would revolutionize the financial world, was created. With or without metaphor, artistic imagination has always been throwing all kinds of epiphanies about the future. It's just a matter of looking at what surrounds us from other perspectives. “La fuerza e incluso la belleza de la obra, en cualquier caso, parecen anidar precisamente en lo que no vemos”[7] [The strength and even the beauty of the work, in any case, seem to nest precisely in what we can’t see] writes critic Graciela Speranza with a resounding vote of confidence in the visionary power of art.

If a cyber currency was created in 2009, ten years earlier, in 1999, technological issues and economic efforts were focused on solving the programming error of a short-sighted software that, when created, had not contemplated its operation in the future. It was believed that because of this error the systems of nuclear power plants, communications, hospitals, and all computers could hatch. To avoid this catastrophe, a fortune was invested worldwide and so, when the clock struck 00:00 on January 1st, many sighed with relief when they realized that the programming error had not triggered the computer apocalypse.

But as we approached the end of the millennium, concerns in Argentina were much more immediate and earthly. On December 10, 1999, the radical Fernando de la Rúa took office as president, a position he would resign two years later with the bank “corralito”, the death of dozens of citizens in demonstrations and a country in turmoil due to the level of conflict. Before the outcome of the huge economic, political and social crisis of 2001, Cecilia Pavón and Fernanda Laguna opened Belleza y Felicidad (B&F), a shop in the Almagro neighborhood of the City of Buenos Aires. There they sold souvenirs, books, and artwork while holding exhibitions and parties with neighbors and artists. That same year Laguna painted Perfecto, from the series Formas negras parecidas a algo, which she exhibited for the first time at B&F. The painting depicts the silhouette of a character with a tongue-testicle-teardrop instead of a head. The work, like all the others in the series, is a composition that relates openwork organic forms, reminiscent of plants, animals, or humans, with painted geometric figures that absorb elements of surrealism and geometric abstraction, a legacy of the modern avant-garde. Laguna seems to say, in a nihilistic spirit, through these paintings: if reason is an attribute that leads humanity to the state in which we are now, it is better to transform ourselves. Dematerialize ourselves.While the virus “puso de manifiesto el agotamiento de un determinado modelo de globalización, cuestionado desde hace décadas por tantos movimientos sociales”[8] [revealed the exhaustion of a certain model of globalization, questioned for decades by so many social movements], it updated all the versions of the end that were already imagined and also those yet to be conceived. It was in 2000 that, in addition to having escaped the cybercollapse, Paul Crutzen, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, unveiled the term anthropocene to designate the geological era in which man-made activities began to generate biological and geophysical changes on a global scale. Regarding the novelties brought by the new millennium, Franco Bifo Berardi identified “los últimos años de la década del 2010 en la que el caos, el dolor y la impostura se desparramaron por todo el planeta”[9] [the last years of the 2010s in which chaos, pain and fakery spread all over the planet].

This is the general context in which most of the works that make up this tour emerged. These are productions that should no longer be read under the wake of the aesthetic paradigm of the art of the 1990s in Argentina and that also move away from trash, which worked as a vehicle as of the 2000s with the installationist boom. It could be, as described by Viveiros de Castro and Déborah Danowski in ¿Hay un mundo por venir?, “esas imaginaciones (que) cobraron nueva vida a partir de los años noventa del siglo pasado, cuando se formó el consenso científico respecto de las transformaciones en curso del régimen termodinámico del planeta”[10] [those imaginations (that) came to life in the 1990s, when the scientific consensus on the ongoing transformations of the planet's thermodynamic regime took shape].

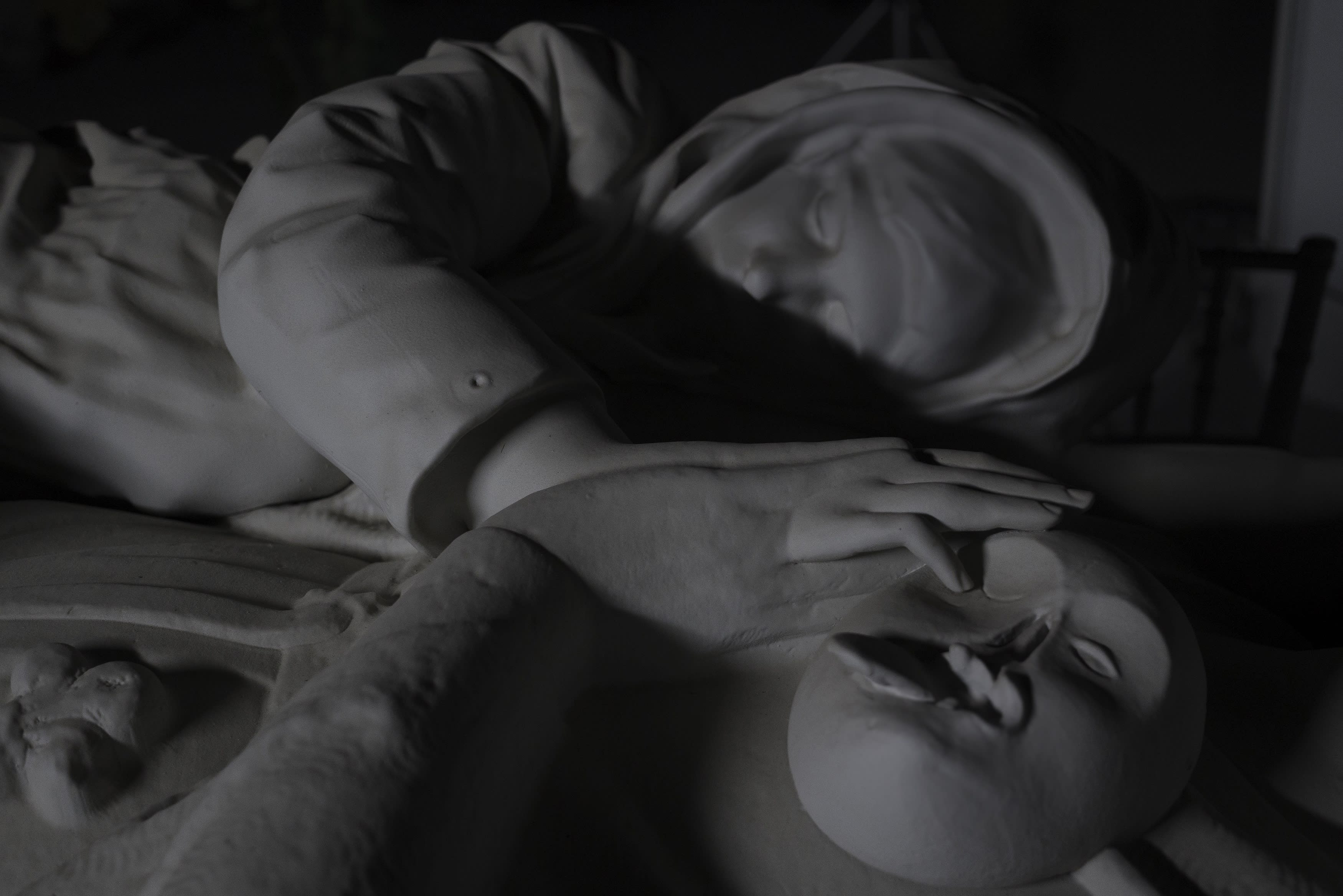

The time frame spans the transition between millennia to the present day and focuses on works with narratives, materials or procedures directly or indirectly associated to dystopian speculations, in which a fundamental feature is the rupture of the representation of linear time (as pointed out by Clara Esborraz in La hora rota). During this period of projections around the future, past and future began to intertwine in landscapes without people or with different beings, such as those created in 2016 by Laura Códega and Nicanor Aráoz. Taciturna y solitaria, and its kneeling, chained woman with plastic bubbling out of her body–a body that by its material composition comes ahead and is associated with the disturbing vision Cronenberg’s Crimes of the future shares in 2022 about the human body and the intervention of art in this transformation–are entelechies without time, with nothing and no one around them.

If the present becomes suffocating and the future, as predicted by scientists, unimaginable, the works can build different experiences on the perception and configuration of the present and the future. Some works sensitize or, as Vinciane Despret[13] would say when he teaches us to look at birds, make desirable other modes of attention; they alert or alter, they stage the past, present and future, modifying our time and space perception. They pivot between reverie and violence, they cancel the distinction between the living and the dead, nature and culture, the human and the non-human, fantasy and the real. They account for a time of transition, they bring us closer to other ways of being, they show the distance from the previous world. “Libertad es saber huir de los fantasmas” [Freedom is knowing how to escape from ghosts], Emmanuel Biset enthusiastically and loudly quoted Anna Tsing at the end of his seminar. The pieces that take part in this journey give shape to the unimaginable; they strengthen us as they enliven our fantasies.

November 2022

[1] Berardi, Franco (2021). La segunda venida. Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, p. 96.

[2] Excerpt from the conference “Anthropocene: Arts of living on a Damaged Planet”, at the University of California. https://youtu.be/6BW8YmRAoW4

[3] Harman, Graham (2010). Towards Speculative Realism: Essays and Lectures. Washington: Zero Books, p. 120.

[4] Butler, Octavia E. (2021). La parábola de los talentos. Madrid: Capitán Swing (first English edition, 1993) and Butler, Octavia E. (2021). La parábola del sembrador. Madrid: Capitán Swing (first edition in English, 1993).

[5] Marder, Michael (2022). El vertedero filosófico. Barcelona: Ned Ediciones.

[6] Colombo, Alejandro (2021). “Copper, a unique window of opportunity for Argentina”. https://panorama-minero.com/noticias/el-cobre-una-ventana-de-oportunidad-unica-para-argentina/

[7] Speranza, Graciela (2022). Lo que vemos, lo que el arte ve. Buenos Aires: Anagrama.

[8] Svampa, Maristella y Viale, Enrique (2020). El colapso ecológico ya llegó. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, p. 13.

[9] Berardi, Franco (2021). La segunda venida. Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, p. 14.

[10] Danowski, Déborah y Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo (2019). ¿Hay un mundo por venir? Buenos Aires: Caja Negra. P.21.

[11] Carried out at Ruth Benzacar Art Gallery.

[12] Seminar “Reading Eduardo Viveiros de Castro”, organized in 2022 at the Kirchner Cultural Center in the framework of the Proyecto Ballena, coordinated by Liliana Viola and Pablo Schanton.

[13] Despret, Vinciane (2022). Habitar como un pájaro. Buenos Aires: Cactus, p. 12-13.